Ion D. Sîrbu & the Small Bearded Priest

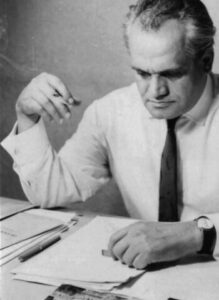

JUNE 2019 was the centenary of the birth of the Romanian dramatist and novelist Ion D. Sîrbu. His is a name not known to the English speaking world, in part because literary life in the Eastern Bloc after the Second World War was a closed door to the West, in part because Sîrbu had fallen foul of the Communist regime almost as soon as it had come to power. He never gave way to falsity and refused to speak against his supervisors when a student at Cluj University; nearly a decade later, he was sentenced to seven years imprisonment for his literary criticism, also for an alleged collaboration with sympathisers of the 1956 Hungarian uprising. During his lifetime Sîrbu (known to his friends as Gary) achieved no commercial success and little favourable review, though he was a quiet hero, literary and otherwise, to many. He saw his days out as a theatre administrator in Craiova and died just a few months before the Revolution of 1989. His writing found a Romanian audience in the heady cultural times after then, and he was translated elsewhere in Eastern Europe but never in Britain. A great deal of Sîrbu’s writing was destroyed by the state police, only some of what was taken from him did he manage to redraft. Apart from his theatre work, only four novels (including two for children) survive, one early novella, a volume of short stories, and some mining reportage; his diaries and now letters have been printed. His most impressive book is Adio, Europa!, an allegorical novel rather like The Master & Margarita; like Bulgakov’s novel, it was published posthumously.

JUNE 2019 was the centenary of the birth of the Romanian dramatist and novelist Ion D. Sîrbu. His is a name not known to the English speaking world, in part because literary life in the Eastern Bloc after the Second World War was a closed door to the West, in part because Sîrbu had fallen foul of the Communist regime almost as soon as it had come to power. He never gave way to falsity and refused to speak against his supervisors when a student at Cluj University; nearly a decade later, he was sentenced to seven years imprisonment for his literary criticism, also for an alleged collaboration with sympathisers of the 1956 Hungarian uprising. During his lifetime Sîrbu (known to his friends as Gary) achieved no commercial success and little favourable review, though he was a quiet hero, literary and otherwise, to many. He saw his days out as a theatre administrator in Craiova and died just a few months before the Revolution of 1989. His writing found a Romanian audience in the heady cultural times after then, and he was translated elsewhere in Eastern Europe but never in Britain. A great deal of Sîrbu’s writing was destroyed by the state police, only some of what was taken from him did he manage to redraft. Apart from his theatre work, only four novels (including two for children) survive, one early novella, a volume of short stories, and some mining reportage; his diaries and now letters have been printed. His most impressive book is Adio, Europa!, an allegorical novel rather like The Master & Margarita; like Bulgakov’s novel, it was published posthumously.

I read recently of a lovely reminiscence by Sîrbu. As an eighteen year-old apprentice he was told to rub smooth pieces of shaped, cast iron in his workshop, a never-ending, summer’s length, repetitive undertaking with an obsessive footnote: the dust was to be removed at all times. Sîrbu described this work schedule as one of “punishment and endless chore,” and its memory caused a recurrent, fevered hallucination in his later years.  The workshop owner was present often, accompanied always by a “small, bearded priest,” and Sîrbu remarked bitterly that “this small and evil pope controlled us.” Thirty years after this ordeal, when visiting Constantin Brâncusi’s wonderful public sculptural triptych in Targu-Jui, Sîrbu gazed up from underneath the concluding piece, Brâncusi’s The Infinite Column, which he had studied hitherto only from afar. He was struck with awe. “Suddenly I felt sick,” he wrote, for he had recognised the pieces he had bled his fingers upon as a young man, when Brâncusi’s priest-like posture had been as a fussy, cruel catechism. Sîrbu had been unaware that he was handling the unformed skeleton of Brâncusi’s trapezoidal and beautiful vision of the infinite; before that moment the seventeen pieces – he had worked on each of them – represented only toil, “torture” and the temporal.

The workshop owner was present often, accompanied always by a “small, bearded priest,” and Sîrbu remarked bitterly that “this small and evil pope controlled us.” Thirty years after this ordeal, when visiting Constantin Brâncusi’s wonderful public sculptural triptych in Targu-Jui, Sîrbu gazed up from underneath the concluding piece, Brâncusi’s The Infinite Column, which he had studied hitherto only from afar. He was struck with awe. “Suddenly I felt sick,” he wrote, for he had recognised the pieces he had bled his fingers upon as a young man, when Brâncusi’s priest-like posture had been as a fussy, cruel catechism. Sîrbu had been unaware that he was handling the unformed skeleton of Brâncusi’s trapezoidal and beautiful vision of the infinite; before that moment the seventeen pieces – he had worked on each of them – represented only toil, “torture” and the temporal.

This last weekend Ion Sîrbu was celebrated in his home town of Petrila, once a centre of Romania’s declining coal mining industry. A museum is sited in Sîrbu’s old house, now festooned with artwork by its curator, Ion Barbu, who is the Romanian not-so-shy Banksy. In the neighbouring town of Petrosani an impressive theatre is named after Sîrbu; here there was a magnificent concert and some drama. This was a celebration of community, regeneration, individuality and creativity, but, above all else, of a writer who might sum up much of the heartbeat that is Romania.