From Straight Lines we Make Curves: an Appreciation of Michael Garrick

ENGLISH JAZZ PIANIST and composer Michael Garrick, a pioneer in mixing jazz with poetry recitations and large-scale choral works, died in November 2011. For the non-cognoscente his compositions could be overly complex, often angular, and his rigorous belief in true improvisation made his work at times inaccessible to the mainstream; yet in concert, eyeball to eyeball, he was able to break barriers. In my opinion he was the finest non-American jazz composer of all time with an extensive body of work, and as pianist and band leader truly world class. This post relates to an interview I had with him in 2003, when he had just turned seventy: for thirty years or more he had been put on ice by the British jazz fold, and the doors that had been opened to him in previous times had, if not firmly shut, been left only slightly ajar. In the last decade of his life he received some of the praise that had been denied him hitherto, and he was delighted to receive an MBE the year before his death (Michael was surprisingly a staunch Royalist). It is now easy (and apt) to recall Brian Morton’s assessment of his achievements in The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD: “When the Big Audit is completed, Britain will find itself in trouble for not having disclosed a national asset on the scale of Michael Garrick …” It thrilled me that I got to know him, for he was generous and kind in all things, and the quality of his music only a hint of his qualities as a person.

photograph by Sisi Burn

BACKGROUND

Michael Garrick’s adolescent love affair with jazz is a tale shared by much of middle class England in the post-war years, when national service was often the only means to have this affair requited. Swing and boogie-woogie held a “magnetic attraction, but I had no means of getting near it,” he says; Pine Top Smith and Meade Lux Lewis (he will still rattle off Honky Tonk Train Blues if you let him), Lionel Hampton and Harry James, whose music “thrilled me to death,” all crossed his path leaving indelible stains on his youthful psyche. He had fallen for the siren’s song, did not know what jazz was, but knew that he wanted to play it. To this day he is rather proud of the fact that he was expelled from Eleanor B. Franklin-Pike’s piano lessons for inflicting Glenn Miller’s In the Mood upon fellow pupils at a musical soiree; but more seriously his parents disapproved of such high spirits and tried to put him off. In deference to this musical apartheid both at home and within the educational establishment, Garrick was adroit enough to sidestep the issue by not studying music at university, where musical faculties displayed the sign “bebop not spoken here.” Yet his ambition to become a dance band pianist, or even better to play jazz, was undiminished, and to this end he practised his arpeggios, put himself through grade eight exams after national service, and embarked on a degree in English literature at University College, London.

While a student Garrick formed his first quartet, in part a carbon copy of the Modern Jazz Quartet, with the novice pianist aping the economy of John Lewis’ lines and Peter Shade, “who luckily was a raver,” providing the pyrotechnics on vibes. English folk song, Greensleeves, Barbara Allen and Bobby Shaftoe, plus Now’s The Time and his own Wedding Hymn (which became part of Jazz Praises), were in the repertoire. Playing opposite Joe Harriott’s group at the Marquee in 1958 and 1959 opened his eyes, and his own musical development through the 1960s saw the Walls of Jericho come tumbling down as Garrick raced from one project and one group to another: Poetry and Jazz recitals to his celebrated Jazz Praises, small ensemble compositions to large-scale oratorio projects infused with a jazz passion, and many recordings both as session leader and with the Don Rendell and Ian Carr Quintet.

GARRICK’S ‘ENGLISHNESS’

Yet the foundations upon which Garrick has built his career have remained secure and have changed very little since the late 1950s and early 1960s, for at the heart of Garrick’s playing is a wonderful and unique brand of ‘Englishness’, of democratic invention, boundless adventure and a sense of place. For sure Garrick had the awareness to take on board all that the American jazz heritage could offer, but he did more than just assimilate this culture. These sounds were distilled through his own personal experience, of course; but more importantly through his own cultural experience, and his brand of jazz has always been shaded by the pastoral greens and social mores of his English and urbane upbringing. The younger Garrick’s partial ignorance of the jazz greats may have helped him here, for serious listening to the classic recordings of the past was a luxury that fell upon him slower than perhaps most: he did not become awake fully to Parker’s gospel until after he had embarked on a professional career, and much of Ellington’s oeuvre he did not discover until his late twenties – a source of retrospective relief, as Garrick feels that he may have wilted when faced with the challenge of Ellington’s achievements at an earlier stage of his development.

British jazz of the late 1950s, as observed by Ian Carr in his book Music Outside, tended to be drawn to the sounds of America rather like a moth to a flame. Such generalizations, of course, do not always stand up against rigorous discussion; but if prototype Charlie Parkers were only occasionally the order of the day – and photocopies of Parker were not the sole preserve of the English! – an overly-deferential respect was paid to the American jazz dream, and breaths of musical self-worth were not drawn deep in the jazz clubs of Britain at this time (and perhaps still today). In cultural terms Garrick thus stands head and shoulders above many of his peers as a true representative of the diasporic spirit of jazz, that unwieldy cultural monster driven by its own constant and innovative momentum. Garrick’s crowning achievement in jazz, distinguished if measured by any criteria, is its impressive and respectful disrespect displayed towards its inherited litany of American musical hierarchy. To him, a jazz musician in England, folk song and church music are as relevant as the blues and tin-pan alley; and his music has always represented the England with which he is familiar, an England with a rural and industrial history, and a fading colonial empire. Thus Garrick’s place of birth, Enfield, its fish and chip shop sitting snugly with its Indian take-away, becomes as much a part of jazz history, for him and for us, as Congo Square in New Orleans or The Grand Terrace Ballroom in Chicago. And this perhaps highlights the problem with much jazz history as perceived and written. Its restless musical etiquette of enriched harmonies – Armstrong’s stomping, flattened sevenths, distressed by Parker’s bebop, made dissonant and dissolute courtesy of Ornette Coleman, today dewy-eyed and retrospective – has too often been shaped by a chronological narrative, which sidesteps the far more interesting and contentious issue of geography, or roots, that is a sense of place and culture. Michael Garrick alludes to the issue of ‘roots’ in his brief liner note to the recent Gilles Peterson anthology Impressed, a collection of recordings mined from the British jazz archive of the 1960s, including three tracks by Garrick himself. “‘Soul’ is a very fluid commodity,” he writes, and Garrick’s ‘soul’ swings with a firm and content English accent.

THE JAZZ LIFE

Gilles Peterson, interviewed recently, feels that the British jazz artists he champions from the 1960s did “live the jazz life… They presented a belief in the movement.” Garrick for one has never lost sight of his own musical fantasy, and if others of his generation flirted with, or were even hijacked by, the strains of rock and electronic gadgetry (and some, it has to be said, danced to this tune with clogs rather than Astaire’s dandy footwork), he remains until this day as active and as consumed with his music as ever, and his adventurous brief to expand its social and artistic gamut remains strong. He claims that he has never been “driven, that’s too harsh a term; obliged, I would say.” There is realism, too: “as you get older you realise there is no retreat, you’re stuck with it.” When incapacitated with severe back problems in 1980 (Norma Winstone, Ronnie Scott and others helped him financially with a benefit concert at the 100 Club) or when the tank has run empty, the times when he feels that “actually what you’re doing is insignificant and who’s going to bother with it anyway,” he has ridden through his periods of despair. In reality, of course, the jazz life, romanticized and embroidered, is “almost drudgery, and the reason you keep on doing it is because when you actually achieve what you want … playing with other people or, in my case as a writer, hearing other people playing your music, well then the ‘up’ for that is so positive: that’s what enables you to carry on.”

Gilles Peterson, interviewed recently, feels that the British jazz artists he champions from the 1960s did “live the jazz life… They presented a belief in the movement.” Garrick for one has never lost sight of his own musical fantasy, and if others of his generation flirted with, or were even hijacked by, the strains of rock and electronic gadgetry (and some, it has to be said, danced to this tune with clogs rather than Astaire’s dandy footwork), he remains until this day as active and as consumed with his music as ever, and his adventurous brief to expand its social and artistic gamut remains strong. He claims that he has never been “driven, that’s too harsh a term; obliged, I would say.” There is realism, too: “as you get older you realise there is no retreat, you’re stuck with it.” When incapacitated with severe back problems in 1980 (Norma Winstone, Ronnie Scott and others helped him financially with a benefit concert at the 100 Club) or when the tank has run empty, the times when he feels that “actually what you’re doing is insignificant and who’s going to bother with it anyway,” he has ridden through his periods of despair. In reality, of course, the jazz life, romanticized and embroidered, is “almost drudgery, and the reason you keep on doing it is because when you actually achieve what you want … playing with other people or, in my case as a writer, hearing other people playing your music, well then the ‘up’ for that is so positive: that’s what enables you to carry on.”

A BROAD CANVAS

Garrick has always sought to broaden the appeal of jazz and give it a wider social currency, and his peripatetic jazz life has been punctuated by opportunities to paint on a larger canvas and mix his musical palette. His Jazz Praises projects from the 1960s, which actually predate Ellington’s sacred concerts, first gave him the chance to use choral voicing in a jazz environment and found its creator in the organ loft of St Paul’s in 1968, a concert caught successfully on disc. In 1961, with Joe Harriott and Shake Keane augmenting his trio, he became musical director of Jeremy Robson’s Poetry And Jazz In Concert, a roadshow that involved setting music to poems written and recited by, among others, Laurie Lee, Spike Milligan, Dannie Abse, Vernon Scannell and Adrian Mitchell. An unlikely affinity was forged with one scribe, John Smith, who wrote a set of poems for the quintet called Jazz For Five. A succession of collaboratory projects followed in its wake including the cantata commissioned by the Farnham Festival, Mr Smith’s Apocalypse. Other large-scale pieces, involving strings or full orchestra and chorus, have also been commissioned along the way, and many of his ideas, such as Bovingdon Poppies (1993) or Linda (commissioned this year by the Farnham Festival), have been on his mind for many years before the opportunity to compose them presented itself.

It is both the sheer weight of Garrick’s output and its breadth which astonishes most: he is, without question, Britain’s answer to Ellington, and only Mike Westbrook can begin to compare. His big band, formed in 1985, fits in to the narrative of his development and is the obvious outcome of the work he was writing in the early 1970s for his sextet/septet – with Art Themen, Henry Lowther, Don Rendell and Norma Winstone (whose voice Garrick used instrumentally to wonderful effect, a device never taken up elsewhere so comprehensively) – where multi-textured instrumental sound is created. The arrangements are deft and accomplished, the music never rests on its laurels but constantly challenges the listener with interweaving lines and contrasting textures. It is this sense of contrast, of light and shade, as though there are contradictory forces at its heart, that is the kernel of his music. Improvisation challenges composition and form, and surprise challenges accepted practice (how many reviewers of his recorded work do we see recoil partly from this?), almost as though he is wrecking his ship on otherwise calm waters.

COMPOSITION

Much of Garrick’s music is inspired by the written word, poetry often its seedling. “A poem has everything – structure, feelings and a clear focus of what everything is about… All you have to do is hang the music on it.” His music tends to be thematic, it tells a story, and not often are his compositions merely academic exercises; some though are written for fun, like the recent Count 77, a sensational eleven-bar Caribbean jaunt in 7/4 time. (As an aside, his performance of such pieces offers a freedom and lucidity that Brubeck, for instance, rarely touched in his forays into irregular time.)

Garrick has never felt pigeon-holed into a narrow jazz idiom: “I just write,” he says simply. His writing is instinctive; he insists that the “spirit of the music wants to come through and it finds its own form;” yet he mistrusts people who claim that jazz music is magic plucked from the air, involving little industry and discipline. He himself believes in practice, an understanding of first principles and the underpinning of music with a coherent form. And he does not see his composing as standing apart from his performing, “it is a void question, the two things are absolutely integral.” If composing is a lonely business (“you sit on your arse all day”) vitality comes from performance, and as an improvising musician he has the “freedom to be a composer all night from the very first note.”

Garrick has never felt pigeon-holed into a narrow jazz idiom: “I just write,” he says simply. His writing is instinctive; he insists that the “spirit of the music wants to come through and it finds its own form;” yet he mistrusts people who claim that jazz music is magic plucked from the air, involving little industry and discipline. He himself believes in practice, an understanding of first principles and the underpinning of music with a coherent form. And he does not see his composing as standing apart from his performing, “it is a void question, the two things are absolutely integral.” If composing is a lonely business (“you sit on your arse all day”) vitality comes from performance, and as an improvising musician he has the “freedom to be a composer all night from the very first note.”

He studied at Berklee College in the United States for two periods in the mid-1970s when Mike Gibbs was composer in residence. He crammed his timetable with all that was on offer – orchestral writing, arranging, the use of synthesisers, even a study of Schoenberg. Much of what he learnt confirmed and shaped much of his own knowledge gained through experience. His inquisitiveness is practical rather than academic, and he would contend that jazz musicians should know of theory by intuition if not by name, citing as a prime example the late altoist Bruce Turner who knew neither notation nor chord symbols.

He made a study of Indian music in the 1960s before the Beatles made India an attachment to their lifestyle, and much of the Rendell/Carr Quintet’s repertoire is inspired by Indian ragas; Black Marigolds, perhaps his best-known piece, is a “self-conscious parody.” He learnt Parker’s solos by rote, not such an uncommon feat for a jazz musician, but his absorption of twentieth-century classical compositional theory, if idiosyncratic and erratic, is. Not too many jazz musicians are familiar with Messiaen’s six modes of limited transposition, Scriabin’s ‘Prometheus’ chord or Nicholas Slonimsky’s Thesaurus of Scales and Melodic Patterns (a book he refers to only, I suspect, to tell the story of its author’s party-piece, which was to play the right hand of Chopin’s Black Keys study with an orange!).

Garrick’s music sits awkwardly in today’s jazz world. If it is not complex neither is it straightforward, and in some respects he stands aside from the mainstream and his music has been perceived as an acquired taste, perhaps the fate of all individualists. But neither the mystique nor cliquish respect that ‘difficult’ music bestows upon some sits at all easy with him, and he believes that face-to-face he can “disarm an audience.” It can only be ironic that for decades he has travelled the country playing and teaching jazz in school classrooms! He is aware that in some quarters of the jazz press there has been a reaction to his musical quirks, and also that music which demands attention from the listener, even if it swings, induces an element of fear. Of his own musical idiosynracies Garrick is unapologetic; and of his use of so many tricks of his trade, his seemingly endless desire to surprise with irregular time patterns and unique forms and structure – which at times has perplexed critics of his music – he says that it seems “to need to be done, there is no other justification, and I’m by no means at all ‘fed up’ with the old jazz tradition.” He has never resorted to ‘repertoire jazz’, and the arrangements he makes for his big band of, say, the Ellington classics are novel interpretations and never mere reworkings.

TEACHER

Mindful of his own troubled route to jazz, Garrick has always devoted time and energy to sowing its seed, both in schools, with his Travelling Jazz Faculty formed in 1965 to entertain and teach children the fundamentals of his music in their classroom, and at college level, having held teaching posts at the Royal Academy of Music, the Guildhall and Trinity College of Music. In 1975 he instigated a jazz course for the Wavendon All Music Plan at John Dankworth’s request; he was one of the prime movers in the establishment of the Associated Board’s jazz examinations in 1999; and for over a decade he has organized two weeks of tuition each year at his own Jazz Academy based at the Beechwood Campus in Tunbridge Wells. It has “become an integral part” of his professional life, he says, and there can be few jazz musicians who have spent more time developing young talent than Garrick. To this end his crowning achievement, of course, may be his big band.

PIANIST

As pianist Garrick has matured with age: “gradually you develop more confidence in your own impulses,” he says. The hustle of youth has dimmed and his playing is now more rounded than ever, takes on a full eight-octave compass, and makes the listener aware of a voice that has thought through its stylistic position and is confident with it. Nevertheless, he remains in awe of others, not just the “huge looming figures from the past” who include the two-fingered Lionel Hampton and George Shearing, but also of his contemporaries: Bill Evans, “who blew me away,” Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea and, to a lesser extent, Keith Jarrett. He cites fellow-Brit John Taylor as a pianist for whom he has total respect: “his originality and accomplishment are at least on a par with what was coming through people like Corea,” states Garrick, who himself has tried to adapt to the “John Taylor vein of thinking.” And yet the striking feature of Garrick’s playing is that he sounds like nobody else, he only sounds like himself; the angularity of Stan Tracey’s post-bebop lines occasionally surface, but the edges are softened by the respect Garrick displays for his piano and the attention he gives to dynamics, a delightful touch, and pedalling. His near total abstinence from well worn or clichéd phrases, used by so many pianists as a crutch or as a resting point along the way, is immediately apparent. There are no effusive runs à la Peterson, and he works to ensure that “finger patterns,” the detritus of the jazz pianist’s mechanistic mind, do not come too close to the surface: when inclined he plays Mozart, for the love of it, and so that his hands are doing things “that aren’t in your repertoire of shapes.” Technique is a “kind of mirage,” he says, but then Garrick possesses the imagination, as did his hero Bill Evans, never to fall back on it. A constituent part of his style is his ambidextrous armoury: both left and right hand can play equal measure in his stylistic cloak. His left hand can roam mercilessly free, can complement, accent, interpose and even argue with the flow of improvisation when called upon. This is a point worth making if only because many jazz pianists, including some of the finest, have never been able to involve effectively both hands in the improvisatory process, either through inclination, through habit, or because it has never been required of them from the context within which they play. Garrick is not frightened of silence and has built in to his style the need for it and the confidence to

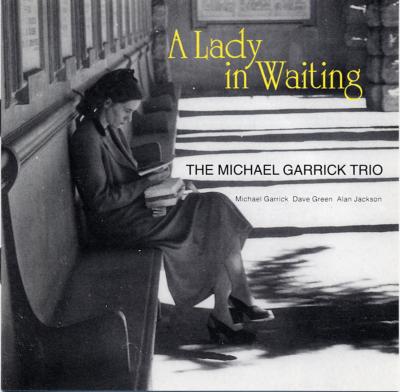

As pianist Garrick has matured with age: “gradually you develop more confidence in your own impulses,” he says. The hustle of youth has dimmed and his playing is now more rounded than ever, takes on a full eight-octave compass, and makes the listener aware of a voice that has thought through its stylistic position and is confident with it. Nevertheless, he remains in awe of others, not just the “huge looming figures from the past” who include the two-fingered Lionel Hampton and George Shearing, but also of his contemporaries: Bill Evans, “who blew me away,” Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea and, to a lesser extent, Keith Jarrett. He cites fellow-Brit John Taylor as a pianist for whom he has total respect: “his originality and accomplishment are at least on a par with what was coming through people like Corea,” states Garrick, who himself has tried to adapt to the “John Taylor vein of thinking.” And yet the striking feature of Garrick’s playing is that he sounds like nobody else, he only sounds like himself; the angularity of Stan Tracey’s post-bebop lines occasionally surface, but the edges are softened by the respect Garrick displays for his piano and the attention he gives to dynamics, a delightful touch, and pedalling. His near total abstinence from well worn or clichéd phrases, used by so many pianists as a crutch or as a resting point along the way, is immediately apparent. There are no effusive runs à la Peterson, and he works to ensure that “finger patterns,” the detritus of the jazz pianist’s mechanistic mind, do not come too close to the surface: when inclined he plays Mozart, for the love of it, and so that his hands are doing things “that aren’t in your repertoire of shapes.” Technique is a “kind of mirage,” he says, but then Garrick possesses the imagination, as did his hero Bill Evans, never to fall back on it. A constituent part of his style is his ambidextrous armoury: both left and right hand can play equal measure in his stylistic cloak. His left hand can roam mercilessly free, can complement, accent, interpose and even argue with the flow of improvisation when called upon. This is a point worth making if only because many jazz pianists, including some of the finest, have never been able to involve effectively both hands in the improvisatory process, either through inclination, through habit, or because it has never been required of them from the context within which they play. Garrick is not frightened of silence and has built in to his style the need for it and the confidence to  use it – and plenty of it. Jazz piano he likens to speech: the aim is to exclude all the stammers and nervous interjections, the slang and its hesitancies. But speech is part of conversation, and Garrick rarely asks his musical partners to provide only a harmonic or rhythmic cushion. To listen to him now in a trio setting [A Lady In Waiting – JAZA 1], not historically his natural habitat, is a real treat, for it is rich ensemble improvisation through and through.

use it – and plenty of it. Jazz piano he likens to speech: the aim is to exclude all the stammers and nervous interjections, the slang and its hesitancies. But speech is part of conversation, and Garrick rarely asks his musical partners to provide only a harmonic or rhythmic cushion. To listen to him now in a trio setting [A Lady In Waiting – JAZA 1], not historically his natural habitat, is a real treat, for it is rich ensemble improvisation through and through.

HOMILY

Michael Garrick has been at the forefront of British jazz for over forty years. He is a pianist of manifest qualities, an improvising musician of wit and invention, and has led or been part of some of the most staple bands of this period. These are accolades rare enough. But his reinvention of the jazz experience in English terms and his width and achievement in composition are without parallel in British jazz of this or any other period. Had he been born in a different period or in a different place he would have been championed further. As it is, he is not even merited a footnote in the recent A New History Of Jazz by Alyn Shipton, yet his achievements have played a part in the developing narrative of the music, and within the context of our own British shores are significant.

Garrick’s quest has been for first principles: “it’s touchingly ironic,” he writes, “that the ‘new’ harmonic sounds [in modern jazz] so assiduously sought for devolve to a handful of already-existent scales.” He found Rudolf Steiner’s Apocalypse of St John in a bookshop many years ago; always deeply interested in faith and creation myth, he found in it a “sphere of knowledge that all hangs together.” He wonders at Steiner’s theories of Projective Geometry (“why didn’t we do this at school, it’s beautiful stuff?”), which invoke for Garrick a sort of magic: “from straight lines we make curves,” he marvels. This also is the challenge he has set for his music. Good humoured, all-embracing, exhibiting curiosity and posing conundrum, Garrick’s music, to borrow from Churchill, is a riddle wrapped in mystery inside a simple scale. We, too, marvel at the magic it invokes.

Album liner notes written for Michael Garrick’s CD release of Jazz Praises.

The Heart Is A Lotus [Michael Garrick Sextet, 1970]

Home Stretch Blues [Michael Garrick Sextet, 1972]

Webster’s Mood [with John Dankworth, TV broadcast 1990]