Louis Armstrong: “The Beginning & End of Music in America.”

LOUIS ARMSTRONG transformed jazz in the 1920s and gave it a direction and purpose. He remains one of its most important figures, changing the nature of soloist and ensemble. He was also able to pursue a career in mainstream entertainment and, health permitting, remain loyal to his true jazz credentials…

Bing Crosby described Louis Armstrong as “the beginning and end of music in America.” Jazz trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie’s dictum, “No him, no me,” remains true and it is often forgotten that Armstrong was not only one of the world’s most charismatic and best loved entertainers for fifty years, but, the mythical Buddy Bolden notwithstanding, was also the first rung of the jazz ladder. He possessed a technical brilliance that fuelled a fierce individuality, and if individuality is the cornerstone of jazz creativity, its early flowering in the hands of Armstrong took the primitive jazz form by the scruff of the neck and gave it direction. He straddled two genres effortlessly, and if it was once held in haughty critical circles that Armstrong peaked in the late 1920s, that his career thereafter strayed from the true jazz fold and amounted to a series of embarrassing (if genial) comic routines, it should be remembered that Armstrong, like early jazz, was rooted in vaudeville. His aim was to entertain and his music walked always this undeviating path. Armstrong’s hankering after popularity is often put down to his humble background; but humour and joy were the heart and flesh of his music (and a companion to his own feeling for life), and it remains true that humour is often so much more telling than more profound utterances. Armstrong breathed and encouraged vitality and wellbeing, and this persona was streaked in both vivid and delicate flashes across his music.

EARLY YEARS

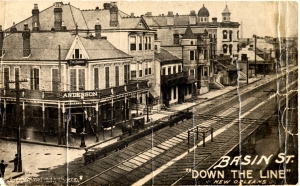

Armstrong’s birth has been the subject of debate, but 4th August 1901 is now accepted following the discovery of a baptism certificate in 1988. Born in the poorest part of New Orleans amongst the brothels and dance halls of ‘Black Storyville’, Armstrong’s early life embraced poverty, deprivation and music. Once a major port feeding the heartland of America, New Orleans was in decline, its prosperity curtailed by the Civil War and the onset of the railways. An embroiled social and racial web had been spun, and from its melee of conflicting class, altered custom and differing musical traditions came the early strains of jazz. “Jazz and I grew up side by side… We were poor and everything like that, but music was all around you.”

His father, a jobbing labourer, left the family around the time of Louis’ birth, and his mother was a domestic and, in all probability, an occasional prostitute. Louis was left in the care of his paternal grandmother when his father returned briefly to the family; upon starting school he returned to his mother, younger sister and a round of stepfathers. From the age of seven until he was twelve, he was taken under the wing of an immigrant Jewish family, the Karnoffskys, who fed him and put him to work, initially selling coal in the streets. They also provided him with his first musical instrument, a tin horn, and enabled him to buy his first cornet from a pawnshop when he was eleven. Having already dabbled in petty street crime, he was charged in January 1913 for firing blanks from his stepfather’s pistol into the air. This incident that was to be the making of him: he was sentenced to serve an unspecified period in the Home for Colored Waifs where his interest in music was to blossom. Having already developed his musical ear singing in a street barbershop quartet as a younger child, he progressed via rudimentary music theory lessons and instrumental tuition to play cornet in its band, whose repertoire included the popular march and ragtime tunes of the day.

His father, a jobbing labourer, left the family around the time of Louis’ birth, and his mother was a domestic and, in all probability, an occasional prostitute. Louis was left in the care of his paternal grandmother when his father returned briefly to the family; upon starting school he returned to his mother, younger sister and a round of stepfathers. From the age of seven until he was twelve, he was taken under the wing of an immigrant Jewish family, the Karnoffskys, who fed him and put him to work, initially selling coal in the streets. They also provided him with his first musical instrument, a tin horn, and enabled him to buy his first cornet from a pawnshop when he was eleven. Having already dabbled in petty street crime, he was charged in January 1913 for firing blanks from his stepfather’s pistol into the air. This incident that was to be the making of him: he was sentenced to serve an unspecified period in the Home for Colored Waifs where his interest in music was to blossom. Having already developed his musical ear singing in a street barbershop quartet as a younger child, he progressed via rudimentary music theory lessons and instrumental tuition to play cornet in its band, whose repertoire included the popular march and ragtime tunes of the day.

THE INFLUENCE OF JOE KING OLIVER

After leaving home in 1914, Armstrong quickly found work amidst Storyville’s nightlife, the red light district of New Orleans, sitting in with his musical heroes. Chief among them was Joe King Oliver, the leading cornettist of the day, who mentored Louis and found him occasional work. A tempestuous marriage to Daisy, a prostitute, was short lived, and when King Oliver moved to Chicago in 1918 following the closure of Storyville, Armstrong replaced him in what then became trombonist Kid Ory’s band. Armstrong’s musical stock was beginning to grow, and his technique, reading skills and musical experience developed further as he played also in Papa Celestin’s band and on the riverboats with Fate Marable and others. In 1922 Louis moved to Chicago to play second trumpet for King Oliver, and two years later he married the band’s pianist, Lil Hardin, who stiffened his ambition and persuaded him to accept Fletcher Henderson’s offer to join his band in New York’s prestigious Roseland Ballroom. His arrival in New York was treated with scepticism by the seasoned professionals of Henderson’s class outfit, but any mistaken view that Armstrong was a musical parvenu and country bumpkin (“He was big and fat and wore high-top shoes with hooks in them, and long underwear down to his socks,” said Don Redman, Henderson’s arranger) was forgotten as soon as Armstrong played. He worked and recorded with singers Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, among others, and his reputation as the leading jazz player of his time became assured as Armstrong’s conceptions of swing and melodic invention unfolded and transformed Henderson’s band. He returned to Chicago in November 1925 to perform in the cabarets and theatres that catered for black audiences, first with Lil Armstrong’s Dreamland Syncopators and then with Erskine Tate’s ‘Little Symphony’ Orchestra. With Tate, Armstrong broadened his vocal range and began to play the trumpet with its more brilliant sound; he swapped to the trumpet completely at some point in 1928.

“Armstrong seemed able to hear what Oliver was improvising and reproduce it himself at the same time. It seemed impossible so I discounted it, but it was true. Then the two wove around each other like suspicious women talking about the same man.” – Eddie Condon

THE HOT FIVE AND HOT SEVEN RECORDINGS

Almost immediately upon his return to Chicago, the OKeh record company contracted Louis to record with studio based bands comprised of well-known musicians familiar with the New Orleans style of collective improvising, including Kid Ory, clarinettist Johnny Dodds and pianist Earl Hines. With Louis as the marketed name, these so-called Hot Five and Hot Seven sides were aimed at the vast numbers of Southern blacks who had migrated northward during and after World War One. Recorded over a period of three years and with each musician paid only 50$ per session, these are perhaps the most influential batch of jazz recordings ever made and changed absolutely the jazz environment. Tracks like Potato Head Blues and West End Blues, flawless and unparalleled, set the new standard: they not only highlighted Armstrong’s brilliant playing but also delineated the soloist’s role in jazz, which was not merely to paraphrase the melody but to improvise above a set of chord changes. With Armstrong as the new figurehead of jazz improvisation, cliché gave way to invention and imagination as Armstrong streamlined his style with his use of time and dramatic pause, and drama was complemented by an emotional purport (especially in the recordings after 1927), and surprise and variety came to the fore. Armstrong had never relied on virtuosity for its own sake (Oliver had told him that “if a cat can swing a lead and play a melody, that’s what counts”) and his ostentatious technique was employed in a more sparse and controlled context, to telling effect.

Almost immediately upon his return to Chicago, the OKeh record company contracted Louis to record with studio based bands comprised of well-known musicians familiar with the New Orleans style of collective improvising, including Kid Ory, clarinettist Johnny Dodds and pianist Earl Hines. With Louis as the marketed name, these so-called Hot Five and Hot Seven sides were aimed at the vast numbers of Southern blacks who had migrated northward during and after World War One. Recorded over a period of three years and with each musician paid only 50$ per session, these are perhaps the most influential batch of jazz recordings ever made and changed absolutely the jazz environment. Tracks like Potato Head Blues and West End Blues, flawless and unparalleled, set the new standard: they not only highlighted Armstrong’s brilliant playing but also delineated the soloist’s role in jazz, which was not merely to paraphrase the melody but to improvise above a set of chord changes. With Armstrong as the new figurehead of jazz improvisation, cliché gave way to invention and imagination as Armstrong streamlined his style with his use of time and dramatic pause, and drama was complemented by an emotional purport (especially in the recordings after 1927), and surprise and variety came to the fore. Armstrong had never relied on virtuosity for its own sake (Oliver had told him that “if a cat can swing a lead and play a melody, that’s what counts”) and his ostentatious technique was employed in a more sparse and controlled context, to telling effect.

Armstrong, accidentally dropping his lyric sheet while recording Heebie Jeebies, gave scat singing – a rhythmic, percussive, wordless and improvised vocal style – its first popular airing (although it was first used by Don Redman in 1924!). Now a bandleader, Armstrong’s voice would be heard regularly on his own records, stemming, so Louis claimed later, from Henderson’s reluctance to let him sing. Heebie Jeebies, recorded in February 1926, was Armstrong’s first hit, selling 40,000 copies within a few weeks; it was coupled with one of the most enduring of all Dixieland-style tunes, Muskat Ramble, based on an old folksong and written by Kid Ory, although Louis claimed later that he had penned it (“Ory named it, he gets the royalties, I don’t talk about it”). But the most influential track for musicians of the 1920s was Cornet Chop Suey: its exhilarating sixteen bar stop-time solo work and ornately phrased eight-note figures demonstrate how far Armstrong was beginning to move away from the New Orleans ensemble interplay of cornet, clarinet and trombone. As an ironic twist, when its test pressing was discovered in 1940, “recommended for rejection” was found to have been scribbled on the label!

Armstrong, accidentally dropping his lyric sheet while recording Heebie Jeebies, gave scat singing – a rhythmic, percussive, wordless and improvised vocal style – its first popular airing (although it was first used by Don Redman in 1924!). Now a bandleader, Armstrong’s voice would be heard regularly on his own records, stemming, so Louis claimed later, from Henderson’s reluctance to let him sing. Heebie Jeebies, recorded in February 1926, was Armstrong’s first hit, selling 40,000 copies within a few weeks; it was coupled with one of the most enduring of all Dixieland-style tunes, Muskat Ramble, based on an old folksong and written by Kid Ory, although Louis claimed later that he had penned it (“Ory named it, he gets the royalties, I don’t talk about it”). But the most influential track for musicians of the 1920s was Cornet Chop Suey: its exhilarating sixteen bar stop-time solo work and ornately phrased eight-note figures demonstrate how far Armstrong was beginning to move away from the New Orleans ensemble interplay of cornet, clarinet and trombone. As an ironic twist, when its test pressing was discovered in 1940, “recommended for rejection” was found to have been scribbled on the label!

The most popular of the sides recorded by the Hot Seven group was Potato Head Blues, which is not in fact a blues at all but a military theme evoking the brass tradition of New Orleans jazz and constructed like a popular song. Wild Man Blues, a collaboration between Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton, truly relegated the ensemble to a supporting role behind the soloist. Guitarist Lonnie Johnson joined Armstrong in late 1927, and he imparted a sense of urgency and drive to the music, as in Hotter Than Hot (a theme based on the final strain of Tiger Rag) where during its climax Louis hits twelve high Cs over eight bars in his final solo. Pianist Earl Hines was one of the few players in the 1920s to match Armstrong in technique, invention and rhythmic drive, and their jousting culminated with superb renditions of Basin Street Blues, noted for the depth of emotion in Armstrong’s vocal, and West End Blues, which opens with a brilliant cadenza made more dramatic by Louis’ restrained solo, a scat conversation with Jimmy Strong’s clarinet and Hines’ reflective solo.

THE BIG STAGE

By the late 1920s, Armstrong’s star was shining bright. Henderson’s attempts to entice Louis back into his fold served only to boost his salary from his regular broadcasts from the Savoy alone to 200$ per week. His ‘circus’ trumpeting with its bravura passages set alongside sweet melodic lines, his sense of musical stage drama with resounding fortissimos and focal points, his singing, his radiant smile and energetic personality were what the white, middle-class theatre and nightclub goers wanted. If Armstrong ever attracted criticism for this, it can only be argued that many of the careers of his fellow jazz stars of the 1920s had, by this time, faded into obscurity.

In March 1929 Armstrong recorded two sides with Luis Russell’s band, including I Can’t Give You Anything But Love, the first time he had recorded a popular song with an accompanying orchestra. This recording provided a template for future Armstrong performances: an opening trumpet solo, a vocal, a brief instrumental chorus followed by a final trumpet chorus and closing stratospheric cadenza, peppered with climactic high notes. Louis’ jazz credentials still shine through as liberties are taken with the beat and phrasing, but from now on he was to rely less on tunes from the black jazz tradition (like Mahogany Hall Stomp) and more on new tunes from Broadway and Tin Pan Alley (such as Body and Soul, All Of Me and Stardust). Hereafter Louis was the star of every show and nearly all of his subsequent recordings highlight his performance and offer limited exposure to his sidemen. Armstrong travelled to New York soon after to play and sing in Fats Waller’s revue show Hot Chocolates, which soon transferred to Broadway. His rendition of Ain’t Misbehavin’ (a hit when recorded later in July) created a sensation, and this marks the point when Armstrong’s career in show business as an entertainer takes off, sometimes at the expense of jazz content. This trend is reinforced with his appearance in feature films – Pennies From Heaven in 1936 with Bing Crosby, for instance, Every Day’s A Holiday in 1938 with Mae West, or Going Places in 1938, where he is featured singing Jeepers Creepers to a horse! In all, Louis appeared in thirty-six movie roles throughout his career, although some were not particularly memorable.

Armstrong’s term with OKeh came to an end in 1933, finishing with some fine recordings, Chinatown, My Chinatown among them. Following lengthy touring and sojourn in Europe (he returns with the nickname ‘Satchmo’, coined by English critic Leonard Feather), Louis signed to Victor records and worked immediately with Chick Webb’s Orchestra, recording Hobo, You Can’t Ride This Train and other numbers. But the early 1930s, set against an economic depression, were troubled times for Armstrong – lawsuits, dishonest booking agents, a troubled marriage, foreign tours, the ricochet from factional rival underworld gangs which necessitated his absence from both Chicago and New York, made life chaotic – and when Joe Glaser, whom Louis had met first in Chicago in 1926, became his manager in 1935, it followed serious management problems and a near ruinous six month lay-off enforced by lip trouble. (Lip health was to become a serious problem for the rest of his career, the result of Armstrong’s showboating technique.) If Glaser was disliked by many, he proved himself to be devoted to Louis throughout his life and allowed him to concentrate solely on his music. By the late 1930s, Armstrong was back on track, and with a sponsored radio show and commercially rooted musical tours with an orchestra led by Luis Russell (replaced in 1940 with a more contemporary big band), his success was truly nationwide. Important players – such as trumpeter Henry ‘Red’ Allen and Sid Catlett on drums – were secured as sidemen, and some sensational records were made which epitomised the swing era, including in 1938 a hitherto forgotten spiritual, When the Saints Go Marching In, which had never been used before in jazz performance and which became an instant hit. Armstrong was contracted now with Decca, whose policy of pairing their stars on recordings meant that Armstrong performed with a welter of artists, some appropriate like Jimmy Dorsey, Billie Holiday or the Mills Brothers, others not so appropriate like The Polynesians or fashionable novelty acts of the day. High quality songs, such as You Won’t Be Satisfied (Until You Broke My Heart), with some wonderful vocal rapport with Ella Fitzgerald, followed, as well as revisiting and revising what he called his “good old good ones”: Struttin’ With Some Barbecue, for instance, first recorded with his Hot Seven in 1927, was recorded again with Luis Russell during the late 1930s. However if recordings of ballads like Sweethearts On Parade in the saccharine manner of dance-band leader Guy Lombardo (whom Armstrong admired greatly) opened up avenues to the jukebox inspired mass-market, there was a sense in which Armstrong, despite his popularity, was left slightly behind in the swing era stampede of the late 1930s and early 1940s. His was essentially a theatrical act featuring his own trumpet and vocals; new generations of trumpeters, like Harry James, Roy Eldridge, and, of course, Dizzy Gillespie, were often more technically accomplished, and Armstrong lost out to the white swing band audience, and a younger black audience was deserting his style of music in favour of rhythm and blues and even bebop (which Louis abhorred). But always Louis weathered the vicissitudes of public taste, and even benefited from them occasionally, such as the revival of Dixieland music during the war years.

THE ALL-STARS

After the Second World War when big band economics fell into decline, a six-piece group called the All-Stars was created to back Louis in 1947 after a celebrated one-off show in New York Town Hall; this group included stellar line-ups, Earl Hines and Jack Teagarden for example, and was directed by cornettist Bobby Hackett. Louis had twenty enthusiastic and punishing years on the road, but the group came to rely more on his showmanship than his jazz. Drummer Cozy Cole commented that Louis only “really played” about eighty percent of the time, but he drew on other strengths; as Humphrey Lyttelton remarked in 1948 after a London concert, “I was particularly struck by the almost Puritanical simplicity of his playing…” Much of the repertoire was culled from his string of hits, such as Blueberry Hill, recorded in 1949, and other renditions of other singers’ hits or songs from stage shows, and numbers that had over the years become his calling cards, like You Rascal You and When It’s Sleepy Time Down South. In the next decade or more a steady stream of hits followed: the Edith Piaf associated La Vie En Rose and C’est Si Bon, both recorded with Sy Oliver’s Orchestra in 1950, A Kiss To Build A Dream On, andMack The Knife, all commercial recordings with little or no jazz content. Songs like I’ve Got The Whole World On A String, recorded in 1957 with the Russell Garcia Orchestra, highlight Satchmo the peerless and awe-inspiring interpreter of a lyric. Armstrong’s own musical tastes were broad, “there’s no such thing as a bad song,” he said, and if ever the material was not as strong as it should be, Armstrong’s performance took over: “Don’t listen to the tune I’m playing, listen to the notes I’m playing.”

After the Second World War when big band economics fell into decline, a six-piece group called the All-Stars was created to back Louis in 1947 after a celebrated one-off show in New York Town Hall; this group included stellar line-ups, Earl Hines and Jack Teagarden for example, and was directed by cornettist Bobby Hackett. Louis had twenty enthusiastic and punishing years on the road, but the group came to rely more on his showmanship than his jazz. Drummer Cozy Cole commented that Louis only “really played” about eighty percent of the time, but he drew on other strengths; as Humphrey Lyttelton remarked in 1948 after a London concert, “I was particularly struck by the almost Puritanical simplicity of his playing…” Much of the repertoire was culled from his string of hits, such as Blueberry Hill, recorded in 1949, and other renditions of other singers’ hits or songs from stage shows, and numbers that had over the years become his calling cards, like You Rascal You and When It’s Sleepy Time Down South. In the next decade or more a steady stream of hits followed: the Edith Piaf associated La Vie En Rose and C’est Si Bon, both recorded with Sy Oliver’s Orchestra in 1950, A Kiss To Build A Dream On, andMack The Knife, all commercial recordings with little or no jazz content. Songs like I’ve Got The Whole World On A String, recorded in 1957 with the Russell Garcia Orchestra, highlight Satchmo the peerless and awe-inspiring interpreter of a lyric. Armstrong’s own musical tastes were broad, “there’s no such thing as a bad song,” he said, and if ever the material was not as strong as it should be, Armstrong’s performance took over: “Don’t listen to the tune I’m playing, listen to the notes I’m playing.”

“When Armstrong takes a first-class song like Stardust, he discards everything a conventional performer would seize. Using mild embellishments and bold improvisation, he rephrases, restates, amplifies, and finally re-creates the melody. He is equally unintimidated by the lyric, which he turns into a pastiche of words and moans. That song, which most performers find difficlut to sing straight, is in Armstrong’s hands, the starting post for an emotional statement far more potent than the original.” – Gary Giddens, Satchmo: The Genius of Louis Armstrong

“When Armstrong takes a first-class song like Stardust, he discards everything a conventional performer would seize. Using mild embellishments and bold improvisation, he rephrases, restates, amplifies, and finally re-creates the melody. He is equally unintimidated by the lyric, which he turns into a pastiche of words and moans. That song, which most performers find difficlut to sing straight, is in Armstrong’s hands, the starting post for an emotional statement far more potent than the original.” – Gary Giddens, Satchmo: The Genius of Louis Armstrong

Work and global travel were relentless, including a forty-five date African tour sponsored by the U.S. Government and Pepsi in 1960. Feted wherever he went, it seemed as though no door was closed to “Ambassador Satch”, even an audience with Pope Pius XII, who was “a little bitty feller I liked so well.” Armstrong suffered a heart attack in 1959, and as general ill health and old age took its toll, his singing became more prominent. The smoke-filled clubs of his youth and his own heavy smoking, growths on his vocal chords and shortness of breath altered his singing style. His voice resembled perhaps more a pastiche of itself as the years rolled by and his trumpet playing was reduced to cameo snapshots; but the emotion, individuality and warmth he imparted to any lyric more than compensated. Insignificant songs like Hello Dolly!, from an otherwise forgettable Broadway musical of 1963, were transformed by his blend of musical alchemy, imagination and taste, and became worldwide hits.

Louis Armstrong’s death in 1971 was mourned the world over, his funeral covered by national American television. It may come as a surprise to the jazz newcomer when, having thought that Armstrong was merely the jovial entertainer who made the world a happier place for singing What A Wonderful World (what a wonderful performance!), he or she discovers that Armstrong is also the primus inter pares of jazz. “Lewis did it all, and he did it first,” was drummer Gene Krupa’s summation of Louis; “…what you’re there for is to please the people,” is how Louis himself put it.

“Armstrong was an artist who happened to be an entertainer, an entertainer who happened to be an artist – as much an original in one role as the other. He revolutionized music, but he also revolutionized expectations about what a performer could be. In the beginning, he was an inevitable spur for the ongoing American debate between high art and low. As his genius was accepted in classical cirlces around the world, a microcosm of the dispute took root in the jazz community, centered on his own behavior. Elitists who admired the musician capable of improvising solos of immortal splendor were embarrassed by the comic stage ham. One reason, surely, is that critics were frustrated (far more than Armstrong ever was) by the fact that relatively few of his fans knew just how profound his stature was.” – Gary Giddins, Satchmo: The Genius of Louis Armstrong