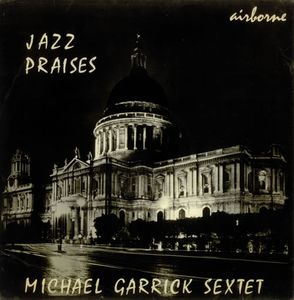

Under an English Heaven: Michael Garrick’s Jazz Praises

MICHAEL GARRICK’s Jazz Praises, composed in the 1960s, is a unique creation. Critic Derek Jewell endorsed it enthusiastically in The Sunday Times and it was broadcast on both television and radio. It also baffled many of those jazz devotees who stumbled upon it. Its setting was, after all, cathedrals or churches, and if not strictly liturgical or even devotional (these were concerts and not conducted services), its subject matter perhaps was deemed too venerable for jazz venues, although it was performed at the 100 Club and at the Phoenix in Cavendish Square. The work is mentioned in thumb nail biographies of its composer but is rarely referred to otherwise, and it never really etched its place in any conscious timeline of British jazz in the 1960s; indeed it is hard to imagine any jazz group today featuring Kyrie alongside a Tubby Hayes’ number!

MICHAEL GARRICK’s Jazz Praises, composed in the 1960s, is a unique creation. Critic Derek Jewell endorsed it enthusiastically in The Sunday Times and it was broadcast on both television and radio. It also baffled many of those jazz devotees who stumbled upon it. Its setting was, after all, cathedrals or churches, and if not strictly liturgical or even devotional (these were concerts and not conducted services), its subject matter perhaps was deemed too venerable for jazz venues, although it was performed at the 100 Club and at the Phoenix in Cavendish Square. The work is mentioned in thumb nail biographies of its composer but is rarely referred to otherwise, and it never really etched its place in any conscious timeline of British jazz in the 1960s; indeed it is hard to imagine any jazz group today featuring Kyrie alongside a Tubby Hayes’ number!

This is the nub of the matter: the suite of pieces that comprises Jazz Praises defies nomenclature, it addresses subjects not ordinarily found in song lyrics and it employs musical forces not readily found in jazz, including a choir – an unwieldy body unlikely to swing and with a fixed musical tablature. Yet at the same time this can only be jazz for it can only be performed by jazz musicians. That Garrick exhibits a familiarity and command of two disparate and dissimilar styles of music does not remove Jazz Praises from the genre; neither does the contemplative nature of this music detract from the fire and spontaneity that is at its heart.

The work, which is a constantly evolving miscellany of individual items, started to take shape as a conscious collection as early as 1962 when Garrick played the harmonium in a small Liberal Catholic church in Camberley. In a congenial atmosphere with freedom to improvise during the formal liturgy, musical ideas and fragments began to coalesce. Anthem, for instance, the stirring organ solo that opened the St Paul’s concert in 1968, came from the introduction to Garrick’s early freeform piece Face In A Crowd, a sequential phrase that Shake Keane had suggested Garrick develop: no discernible chord sequence emerged, only a bass line and ascending melody, and his quintet of the time continued to play it as a freeform piece in a loose 5/4 time. Only when the composer came to familiarise himself with the organ in St Paul’s did it become, in Garrick’s phrase, “more pre-formed.” Some of the movements, like Wedding Hymn (“a fit of passion” from 1960), were composed as complete pieces already; others followed as Garrick borrowed text from the Book of Common Prayer and the Anglican Psalter; and two were to be recorded in 1965 before the St Paul’s performance. With no close knowledge of church music and its tradition and no childhood memories of choir school to fall back on, each movement found its own musical form and was composed in a vacuum, for Garrick relied neither on ecclesiastical precedent nor, indeed, on any jazz form, be it the blues or popular song.

The work might have stayed on the drawing board had it not been for Victor Fox, music adviser for Hampshire, who suggested that Garrick make contact with Peter Mound of St Michael the Archangel Church in Aldershot: it was there he tackled the organ and scored parts suitable for amateur choir. First performed at Aldershot in November 1967 to a good reception (The Sunday Times‘ piece was entitled ‘Ferocity in Church’), Garrick and Mound were emboldened enough to evangelise the four corners of the ecclesiastical kingdom in search of venues, and bookings were received at churches and cathedrals as far flung as Aberdeen, Leicester, Wandsworth, Cambridge and Canterbury. St Paul’s was its fourth outing. The Dean, Martin Sullivan, met them both, considered the music worthy and then programmed Jazz Praises for a festival celebrating youth and music. (He offered also to play drums!)

That the concert was caught successfully on tape at all is a small miracle. Savings were ransacked and a stereo tape machine bought for the occasion, but only a single microphone, suspended across the chancel directly above the performers, was affordable! Most of the excessive echo from the walls and dome of the cathedral was thus negated and the resulting mono recording actually catches well the spirit and spectacular atmosphere of the cathedral, where the music reverberates over the nave and transepts like a thunder sheet. The recorded sound, given its lo-fi resource and lack of technical sophistication, is remarkable: the choir never out of balance with the instrumentalists, the magnificent Henry Willis organ never swamping the other musicians.

Garrick’s use of the organ in its ecclesiastical setting is startlingly inventive. Since the 1940s even the studio pipe organ had rarely been used as a jazz instrument, and those who had recorded with it before then had sought a sound more akin to its use in theatre or silent films, a Wurlitzer sound. Fats Waller reputedly met the organist Marcel Dupré in Paris at the Cathedral of Notre Dame in 1932, but the church organ (Waller’s “God box”) had never played a part in jazz. Exhibiting the curiosity, innocence and delight of a musical parvenu, Garrick experimented with its range and sonorities like a boy with his first Meccano set, first on the two manual organ at Aldershot and later the five manual Voice of Jupiter at St Paul’s. Organist Christopher Dearnley (“a jolly good sort,” recalls Garrick) allowed him unlimited overnight access, via the darkened crypt, to practise). The extremities of the instrument’s capabilities were exploited, from the angelic timbres of the fragile pipes behind the altar to the thundering dome tubas, discovering effects that even Dearnley found remarkable; Behold, A Pale Horse opens with Gothic and shattering overtones, eerie deep vibrations from a cluster of the lowest pedals usher in the foreboding tale of death and destruction from the Book of Revelation. (Incidentally, the 32-foot bombarde stop used to aid the effect was removed soon after 1968 when a new console was installed. Thus this recording enshrines a sound no longer actually playable in the Cathedral.)

Garrick’s use of the organ in its ecclesiastical setting is startlingly inventive. Since the 1940s even the studio pipe organ had rarely been used as a jazz instrument, and those who had recorded with it before then had sought a sound more akin to its use in theatre or silent films, a Wurlitzer sound. Fats Waller reputedly met the organist Marcel Dupré in Paris at the Cathedral of Notre Dame in 1932, but the church organ (Waller’s “God box”) had never played a part in jazz. Exhibiting the curiosity, innocence and delight of a musical parvenu, Garrick experimented with its range and sonorities like a boy with his first Meccano set, first on the two manual organ at Aldershot and later the five manual Voice of Jupiter at St Paul’s. Organist Christopher Dearnley (“a jolly good sort,” recalls Garrick) allowed him unlimited overnight access, via the darkened crypt, to practise). The extremities of the instrument’s capabilities were exploited, from the angelic timbres of the fragile pipes behind the altar to the thundering dome tubas, discovering effects that even Dearnley found remarkable; Behold, A Pale Horse opens with Gothic and shattering overtones, eerie deep vibrations from a cluster of the lowest pedals usher in the foreboding tale of death and destruction from the Book of Revelation. (Incidentally, the 32-foot bombarde stop used to aid the effect was removed soon after 1968 when a new console was installed. Thus this recording enshrines a sound no longer actually playable in the Cathedral.)

Jazz Praises is a first in so many instances. Garrick’s use of the organ remains unique, and those who in more recent times have followed his lead – John Taylor, for instance – have had few opportunities to develop the craft. Jim Philip’s swirling, plangent saxophone solo in Rustat’s Gravesong anticipates the popular cathedral work of Jan Garbarek and John Surman in later decades. Garrick himself, in daring compositions like Underground Streams, developed his use of text and music, the one amplifying the other in a way not often found in the Tin Pan Alley inspired jazz world. And the spirit of Jazz Praises was developed further by Garrick in a succession of large scale choral-based works: Judas Kiss, a lengthy Passion setting, followed soon after; the magnificent Mr Smith’s Apocalypse, a jazz cantata written with poet John Smith and recorded by Argo in 1971, lies dormant in Universal’s vaults; later works like Bovingdon Poppies (the only jazz composition for Remembrance Day) and A Zodiac of Angels (from G. Davidon’s A Dictionary of Angels) and Linda (the story of a child healer) use orchestral as well as choral forces with jazz musicians and singer Norma Winstone. For a composer who claims his career to have been shaped by accident rather than design, these are remarkable achievements and they stand alone in the jazz world. Many of his works, like Jazz Praises, were not commissions: they came about by force of will. That others were thinking along similar lines – Duke Ellington, Mary Lou Williams – is beside the point and is proof again that one idea can strike many chords. For what it is worth, Garrick recorded Wedding Hymn and Anthem with his quintet, organist Simon Preston and the Elizabethan Singers in April 1965 for the Argo label six months before Ellington’s First Sacred Concert.

Above all, Jazz Praises is an English experience, retelling the American jazz dream in an Anglican setting; in a sense it is the English Reformation all over again, Garrick its Henry VIII. Reissues galore and the occasional fashionable endorsement have made British jazz of the 1960s somewhat glamorous again: this is fashion, to be picked up and cast away. But aside from the lip service paid to a decade (and more) of intense and unique creativity – a golden time when British jazz shook off an at times overbearing American mantle and discovered itself – little credence is given to its reality. Garrick is a representative of the true Diasporic spirit of jazz: to him, and for us, St Paul’s is as much a part of jazz history as Congo Square in New Orleans or The Grand Terrace Ballroom in Chicago. To him, a jazz musician in England, church music and folk song are as relevant as the blues and Broadway: Jazz Praises was, indeed, written “under an English heaven.”

Amazingly and by chance, a French TV crew were in St Paul’s and shot some footage.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2LefpHQJzCg

Peter Mound was our music teacher at Farnborough Grammar, and I wellnremember his enthusiasm regarding Jazz Praises. The Michael Garrick Trio played at our school, too, once.