A Love Affair with Libraries

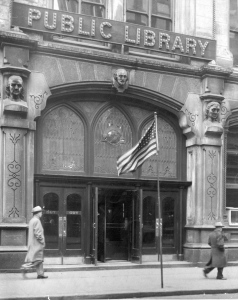

MY FIRST MEMORY OF BOOKS involves libraries. I am sure of it. I may have been given books to throw out of my cot and I may have had books made of plastic to float in my bath; I have no recollection. But I can recall the libraries that festooned my childhood. I say festooned because there is something wonderfully ornamental and overwhelming attached to the architectural image that I hold now of these municipal Mecca. My imagination still will embellish anything from my childhood that involved both volume and order, for these were measurements of wonderment then, stepping stones of astonishment that I might have used to make sense of the world. The public libraries of my childhood had each an astonishment of books – their number too unfathomable for me to even have imagined counting – sat on untold rows of shelves that radiated and furrowed to form corrugations, spirals and vistas, avenues sculpted like the opened ornamental fan my grandmother spread out on her lap. Libraries possessed order that my own world could not contain: rows of solid bookcase, shelves fashioned with purpose, books weighted shipshape and spruce like the parade of keys patterned on my piano at home. Here books stood to attention like the myriad blackbirds that sat on the telegraph wire threaded across my back garden. A library was like a giant playpen that begged you to hide behind any of its rank of books. It was designed intentionally like a maze within which you could get lost.

“I do like to get in a taxi and say, ‘The Library, and step on it.'”

– David Foster Wallace, Infinite Jest

Any sortie to a library involves anticipation. That’s just common sense. Even before you start the library route march or arrive to step inside, you have to plan the task ahead. You have to find your library card, to find your book, make careful note of its return date stamped inside (and make sure, when older, that you have the requisite pocket money to pay off the fine). But these journeys are never solitary: each plays its part in a sequence, a metronomic shuffle of journeys that always culminates with ricochet. A book from a library is like a boomerang, you thrown in its wake.

The ritualization of these journeys may be why libraries remain in my memory as defined moments in time. These visits belong to the fragment of my life when experience was always new and rich, like spring blossom budding in an astonishment of colour. But they linger also as shadows cast inside a padlock; this code is to be broken sometime in the future whenever I feel the need to be nostalgic. Today, it is sentimentality that breaks free as accompaniment to the “childish treble, pipes and whistles” of my sixth act. Those well-intentioned enough to intone against modern day dismantlement of the publicly funded library service, will realise that they rarely (if ever) use libraries anymore; nor even can they pretend that many others do. These childish library memories will encapsulate the maudlin or elegiac before the useful, and, in truth, all that is wished may be to imprint a personal chemtrail of childish delight on a future sky. The respect we show for libraries is like the passing on of a well-chewed toffee humbug: all spittle and saccharine, little grist or anything of the germane. We remember our own hallowed moments and are anxious to let those who follow us share them. Libraries bring out the virtue within us.

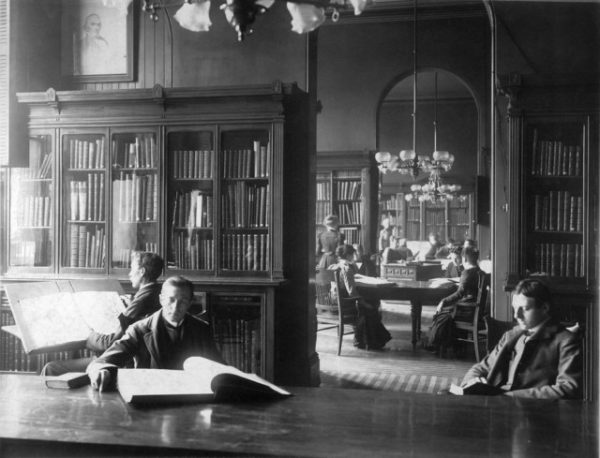

If I step inside a library today, it speaks volumes of my youthful, innocent past. As a young boy, waiting inside them for my mother to sate her gannet greed for Mazo de la Roche or Pearl S. Buck, I would feed my own perversion for titbit snatches of Malcolm Saville, Eric Linklater or any other of my favourite authors. Or gape with fascination at the covers of Compton Mackenzie’s autobiographical Octaves (when pieced together, I could play Scott Joplin on the piano keyboard that decorated the multi-volume covers), or unpick the lattice decoration on the Monica Dickens’ (Mermaid edition) cover. In my youth libraries proffered an overwhelmingly tactile sensation. Each book invited a comforting caress, but importantly only a caress and never more. In a library no one single book stole your heart. A library can inspire deep affection but rarely excites lust. Adolescent lust is rather like a blunderbuss, random and charged. So, libraries to my tender teenage frame represented the urgent clamour and welter of a world opening up, shambolic and frenzied. These spaces, even if curated in a cupboard at the back of a school classroom, but especially if grandly spaced in the town centre, assaulted your mind with a colour that might never have been seen before. Public libraries may have been designed to be curated mausoleums, each book obeliscal and a momento for the past; but in practice, and throughout my sexually charged adolescence, they were kaleidoscopic brothels for my young and promiscuous mind. Libraries are blowholes for the carefree moment. The bell curve of your reading was shaped according to your youthful interest, but a library catered for the general and despite its Dewey numbered gendarmerie – the bibliophile’s attempt at identity politics – a library struggled to be specific. In a library you fell in love with books, rarely a single book.

I’ll never forget the lady librarians of my youth, luscious as they walked their book trolley like a poodle; they radiated ambiguous sexual fallout. An adolescent rite of passage was to stand in a library queue – one of those acned crossing of the equator moments when as a male pubescent pollywog I was presented with my nemesis: the female librarian. Always drop-dead gorgeous, ruby red lipstick and blush, long fingernails, she had a name like Trish, Barbie or Samantha. Standing in the queue, I would hope longingly, lustfully, that Trish, Barbie, Samantha or whichever lady librarian attracted my ardour at the time would sign out my Malcolm Saville. The female librarian was a far more sensuous version of the school matron: she would stamp my borrowing card and the slip attached to the front inside cover like a dominatrix (and she would wobble as she did it, and if I were Craig Raine no doubt I’d write a smutty poem about my effervescent lust, even today, for female librarians). Now, as a shellback, I am still eager to pay any fine and to be a recipient of the extra, dedicated spanking session when I return a late book.

I’ll never forget the lady librarians of my youth, luscious as they walked their book trolley like a poodle; they radiated ambiguous sexual fallout. An adolescent rite of passage was to stand in a library queue – one of those acned crossing of the equator moments when as a male pubescent pollywog I was presented with my nemesis: the female librarian. Always drop-dead gorgeous, ruby red lipstick and blush, long fingernails, she had a name like Trish, Barbie or Samantha. Standing in the queue, I would hope longingly, lustfully, that Trish, Barbie, Samantha or whichever lady librarian attracted my ardour at the time would sign out my Malcolm Saville. The female librarian was a far more sensuous version of the school matron: she would stamp my borrowing card and the slip attached to the front inside cover like a dominatrix (and she would wobble as she did it, and if I were Craig Raine no doubt I’d write a smutty poem about my effervescent lust, even today, for female librarians). Now, as a shellback, I am still eager to pay any fine and to be a recipient of the extra, dedicated spanking session when I return a late book.

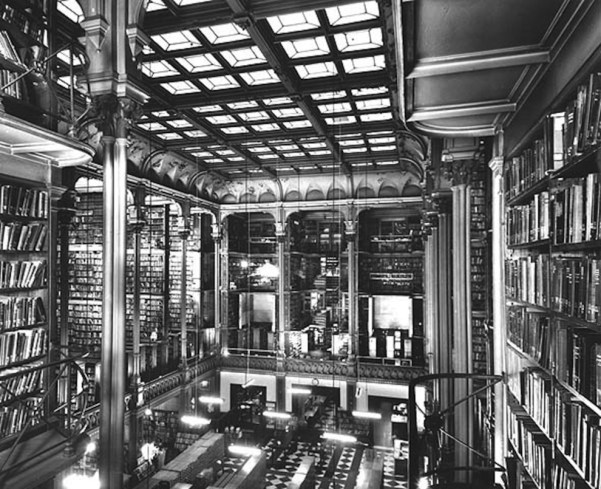

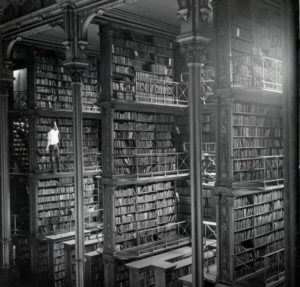

ON THE INTERNET one day I stumble across a collection of photographs taken of old Cincinnati Public Library. This building was bulldozed in 1955. The photographs are startling, greyscale, razor sharp images of silhouetted and bookish colonnades, redolent of past worlds and cultural values. My mouth waters. Shelved trusses are laden with bookish fruit, arched by tomed espaliers: a rich orchard of typography and bound learning.

ON THE INTERNET one day I stumble across a collection of photographs taken of old Cincinnati Public Library. This building was bulldozed in 1955. The photographs are startling, greyscale, razor sharp images of silhouetted and bookish colonnades, redolent of past worlds and cultural values. My mouth waters. Shelved trusses are laden with bookish fruit, arched by tomed espaliers: a rich orchard of typography and bound learning.

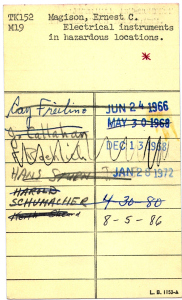

How fitting that the Cincinnati library with its excess of high architecture and bold public statement (it had opened in a building designed originally to be an opera house), had a  tacky, Braillesque entrance sign, an entrance to welcome all tastes. One of the glories of the library is that it is like the nuclear Anglican parish church with its several congregations, one for each Sunday service: the King James early morning Communion, the happy-clappy family service, somber evensong and the tub-thumping evening address. Likewise a public library is radiantly democratic. It serves the homemaker – how to wire a house (if you really want to) or how to snag your woolly jumper while tending your allotment; it serves the blissful – Marcel Proust (unread, note the unstamped borrowing record on its front inside) can be found nearby to Henry Williamson; it serves the dating industry – rows of unheard plays to take along to your next am-dram rehearsal (everyone knows am-dram societies are dating agencies, why else would anyone dress up to recite Sheridan?); gallons of poetry to serve the romantic – you can even call up the poetry of hapless hobo Francis Thompson for goodness sake; and so on. Libraries serve one and all without question or apology. They serve also all denominations of culture, the low and the high and everything in-between.

tacky, Braillesque entrance sign, an entrance to welcome all tastes. One of the glories of the library is that it is like the nuclear Anglican parish church with its several congregations, one for each Sunday service: the King James early morning Communion, the happy-clappy family service, somber evensong and the tub-thumping evening address. Likewise a public library is radiantly democratic. It serves the homemaker – how to wire a house (if you really want to) or how to snag your woolly jumper while tending your allotment; it serves the blissful – Marcel Proust (unread, note the unstamped borrowing record on its front inside) can be found nearby to Henry Williamson; it serves the dating industry – rows of unheard plays to take along to your next am-dram rehearsal (everyone knows am-dram societies are dating agencies, why else would anyone dress up to recite Sheridan?); gallons of poetry to serve the romantic – you can even call up the poetry of hapless hobo Francis Thompson for goodness sake; and so on. Libraries serve one and all without question or apology. They serve also all denominations of culture, the low and the high and everything in-between.

Libraries, even more so than bookshops, have seen mass abuse in recent times. Libraries exemplify the clash of crossover culture that we are witness to today; they have become relics of yesteryear, undermined by the advances of the modern world and struggling to make sense of themselves. We tend to forget that the book itself at its birth did much to destroy how we had lived before. Woodblock printing and Johannes Gutenberg’s early fifteenth century metal printing press stampeded society into a new age, did much to reshape our minds and essentially rewired us: memory was less important, storytelling took a back seat, mythology was muted by hard copy. Now as we witness the printed form lose ground to its digital counterpart, we can determine mass tidal distortion in how we use our minds and how we access information. There is a delicious symmetry of abuse here. To the Luddite mindset, the book is today a wholesome object. It stands for continuity and virtue; it represents the stable mind, dedicated and concentrated; it offers focus, a tunnel vision alongside a peripheral overview. It is to be valued above all other forms of engagement, which otherwise can be unreliable, immature, ill-considered and transient. Above all else the library is not the internet, the home of social media and its perversions, where the lapsed mind can freewheel catastrophically. The internet is the E-number of knowledge that never quite quenches thirst. Yet the book, in its founding day, was considered to be an E-number, all of this and much else. It was considered heretical and louche, dangerous, and it posed a threat to the well-being of those exalted or in power. A comeuppance indeed, and worth noting that if the internet threatens and destabilizes, it need not be anything other than a good thing. To challenge the status quo is so worthwhile and useful. It can make us cherish what we hold dear and distil our thoughts to what is of real value.

Seemingly the internet and all the digital advances of modern life put the library at peril, and today we see County Councils wishing to rid themselves of their duties, crying intemperately, as Henry II had once of Thomas Becket: “who will rid me of this troublesome priest?”

But I see little actual evidence that the digital world has arrested the fate of the book. Indeed the digital world appears as if it is a spectre, a shallow and skeuomorphic confidence trick whose bark is only as loud as its bite. Skeuomorphism is the design concept of making construct objects mimic the sensation, experience or appearance of their real-world counterparts and are used often as attempts to make the new less frightening, or seem familiar and comfortable: clay pottery, for instance, that maintains traits of its wooden counterparts from previous generations; or they may be attempts to break down educational or technical differences, or cultural influences, fresh iconography overwriting past belief systems.

Promoters of the internet tout unashamedly its presentation of the brave and fearless new world; the World Wide Web’s original strength and virtue was to create layers of information so that its users could mine that information as deep as they wished through hyperlinks, a new way of reading the world, a contrast to the rather linear approach of paper text. Yet today the internet has dissolved in to something far less impressive, and reading the news, say, on the internet is as linear as reading, say, the Guardian in its print format (although having written that, I assume that nobody in the right mind would wish to read the dippy, liberal Guardian). The internet has distilled its essence to old static forms and the old architecture of creative thought. It’s like moonshine: tempting but not quite the real thing.

In fact the book seems to be cherished and aped by its digital rivals, even its golden mean dimensions have been copied. Moreover the eBook incorporates non-visual skeuomorphs – the hinged and page-turning movement of a book, its balance and weight, and so on. The movement and sound of a page turning is efficient, of course, and its purpose may offer a sense of geographical balance to the experience of reading what in other cultures would have been described as a scroll, for it is well established that the brain functions better with gobbets of information within a defined boundary. Indeed for all the amazing virtues of digital media (and who would refer to a physical dictionary these days?), it is hopeless at mapping out any physical memory that a reader can attach to the geography of a book.

All this suggests to me that digital formats, however bright and shiny, are not likely to sack the book, and I like Stephen Fry’s observation that the book’s experience will be rather like stairs in a public building: the archaic stair is far from anachronistic and will survive the threat of obsolescence from the more comfortable lift.

But there is far more to it than that. I would posit that most books sold by bookshops in the previous decades have remained unread, and that most have been bought to fulfil a need other than their being read. This seemingly wanton waste of our economy offers a big clue about the book’s real purpose. Our personal libraries consist of what we have invested ourselves in, and serve as reflection of who we are and, more importantly, who we wish to be. Books, above all else, are aspirational objects, and are far more than the custodians of what otherwise can be translated into binary code. The books that we cherish and line our houses with will mirror, or have once mirrored, the aspirations of each of us; the ones that we cull will tend to be those in which we see no self-reflection. So many times I hear still that so many people prefer to read a physical book because they can see not just the book itself, but who they are whilst they read it. And for sure, one thing designers can’t reproduce in the Kindle is this aspirational sensation that the tactile book offers.

The book’s commercial fall from grace in recent times then, I suggest, has less to do with any supposed technical advantage of its digital rival, and more to do with the rise of other much simpler outlets that vie for our aspirational need and attention. The book, of itself, appears to me to be a wonderful and secure piece of technology, finely tuned since Gutenberg’s day. It relies on a power source that is derived from ourselves and not from a battery, and this is the essential difference between the digital and the analogue world: the analogue world breaks down, it falters, it resembles human breath and cadence, but it is at all times responsive in its failures: it breathes. And this is why we respond to the tactile, often clumsy bound book in an emotional way, often in the same way that hi-fi cognoscente respond to the nostalgic echoes and forgiving resonance of vinyl above the CD or download. Neither do books succumb so readily to a commercial theme park where a consumer is tied in to one commercial brand – you buy a Kindle you buy from Amazon, simple. Nor is the book subject to censorship and interference through the back door: it was vaguely humourous that in 2009 Amazon was able to (and it did) delete from customers’ gadgets, copies it had sold previously of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four; a rights issues dispute had embroiled the edition sold. Big Bruv rules OK.

Perhaps it is now that our aspirational yardsticks – that is how we visualize who we wish to be – are to be found elsewhere. Mostly they can be found online with our diarrhoeal jottings on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter or their ilk, carefully self-monitored environments of polished gemstone and fiction, honed to reflect the image we hold of ourselves (and only then, I contend, to serve how we wish others to perceive us). It is this migration of aspiration that is the real threat to the book; the book’s apparent frailty as a piece of technology is almost irrelevant. And this threat applies also to all vessels that the book sails in – be they public libraries or bookshops. And it highlights also perhaps our lack of desire to act as aspirational beings today (but that is another topic).

MY FAVOURITE PICTURE of the Cincinnati collection is this: a gaggle of children wait outside the Library, seated on the building’s front steps. It might be 8:55am, five minutes before the library is yet to open. An approving library porter stands inside gazing out at the children. The children entertain themselves by reading books, their satchels cast aside as debris. The question I ask is this: if today’s world – ubiquitous Wi-Fi, Costa coffee on the hoof, general impatience, the attention span of a gnat, endless digital pleasure and convenience – is a worthwhile replacement for this image? The photograph becomes more than a black and white plate of nostalgia. This is an image that plays easily with our emotion. It is rampant with imagination and youthful zest. Indeed it can remind me of my own love affair with libraries, also the giddy importance of books in my own early years. The joy of reading them with a torch in secret under my bedclothes, that special feeling when a book is nearly finished, the delight felt on turning a crisp opening page.

But above all else, this is an image of aspiration. And behind it: a cathedral comprised of words where, if we are not careful, Thomas Becket may yet be slain again.