Siciliano, Spirituality and Saccharin

AN EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY VOGUE for transcribing Bach chorales or instrumentals for the piano was that meeting point of nostalgia and aspiration. Perhaps their inspiration was a reaction to the crudities of the time and what had been before, as those with sensitivity witnessed the once eternal truths of the past swept away by a tidal wave of political and military cacophony and chaos. These musical miniatures, as well as useful lollipops, were intense moments of focus, and their purpose, for fashion sometimes has purpose, must have been as spiritual sounding boards to reflect the hope needed to confront such heady days. After the First World War virtuosi succumbed to performing these often self-penned and perhaps personalized transcriptions (of Bach especially) – Alfred Cortot, Alexander Siloti, Egon Petri, Myra Hess, Harriet Cohen and many others. Busoni’s overblown reworkings of Bach might have served as a model. The modern piano’s virtues (or, in the case of Godowsky’s transcriptions, its excesses) could be employed without any questioning of how appropriate they might be: the over-indulgent use of a romantic sustain pedal, different tonal voicing, large chords and big stretches, a wide tonal range and heightened dynamic – technical fare not available to the pianist if he wished to stay loyal to Bach’s original voice.

AN EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY VOGUE for transcribing Bach chorales or instrumentals for the piano was that meeting point of nostalgia and aspiration. Perhaps their inspiration was a reaction to the crudities of the time and what had been before, as those with sensitivity witnessed the once eternal truths of the past swept away by a tidal wave of political and military cacophony and chaos. These musical miniatures, as well as useful lollipops, were intense moments of focus, and their purpose, for fashion sometimes has purpose, must have been as spiritual sounding boards to reflect the hope needed to confront such heady days. After the First World War virtuosi succumbed to performing these often self-penned and perhaps personalized transcriptions (of Bach especially) – Alfred Cortot, Alexander Siloti, Egon Petri, Myra Hess, Harriet Cohen and many others. Busoni’s overblown reworkings of Bach might have served as a model. The modern piano’s virtues (or, in the case of Godowsky’s transcriptions, its excesses) could be employed without any questioning of how appropriate they might be: the over-indulgent use of a romantic sustain pedal, different tonal voicing, large chords and big stretches, a wide tonal range and heightened dynamic – technical fare not available to the pianist if he wished to stay loyal to Bach’s original voice.

A devote of such transcribing practice was Wilhelm Kempff. He was feted for his interpretation of the nineteenth century Germanic repertoire and was much recorded (two complete sets of Beethoven sonatas, for instance, in mono and stereo, as well as a near complete cycle on shellac). For much of his career he was hidden from the English-speaking world: his first recital in England was in 1954 only, in America ten years later. Artur Schnabel held him in great esteem, so much so that he requested of EMI that if he himself failed to complete his recording of all Beethoven sonatas, they were to second Kempff to record those remaining, even though his playing, far more lyrical and spontaneous than Schnabel’s, was not the best fit. Alfred Brendel declared that Kempff “played on impulse… it depended on whether the right breeze, as with an aeolian harp, was blowing.”

A devote of such transcribing practice was Wilhelm Kempff. He was feted for his interpretation of the nineteenth century Germanic repertoire and was much recorded (two complete sets of Beethoven sonatas, for instance, in mono and stereo, as well as a near complete cycle on shellac). For much of his career he was hidden from the English-speaking world: his first recital in England was in 1954 only, in America ten years later. Artur Schnabel held him in great esteem, so much so that he requested of EMI that if he himself failed to complete his recording of all Beethoven sonatas, they were to second Kempff to record those remaining, even though his playing, far more lyrical and spontaneous than Schnabel’s, was not the best fit. Alfred Brendel declared that Kempff “played on impulse… it depended on whether the right breeze, as with an aeolian harp, was blowing.”

Without doubt the bedrock of Kempff’s musical life was J. S. Bach. By the age of ten he could perform from memory all of the 48 Preludes and Fugues, and astonishingly as a party trick he was able to transpose each into any key and perform them (as can Barenboim). He returned to his favoured Bach late in life with a cycle of dramatic recordings, and he died a very wise and very old man aged 95 in 1990. During the 1930s – though published only in the early 1950s – he arranged ten Bach chorales and three Bach instrumentals. He had admired greatly Busoni’s much more florid transcriptions of Bach (he had received lessons from Busoni when a child), but Kempff’s musical offerings stayed faithful to the original score and are (mostly) humble in their approach to the keyboard, respectful to the smaller technical resource available to Bach. He had been in awe of Busoni as much (if not more) for his spirituality as for his skill as an arranger; it was Busoni’s almost sacred aspect which, remarked Kempff, explain the transcriptions’ profundity. Kempff’s arrangements of Bach, too, had a devotional deportment for him; he was a Lutheran and a very fine organist, as had been his father (who was a church minister) and his grandfather professionally.

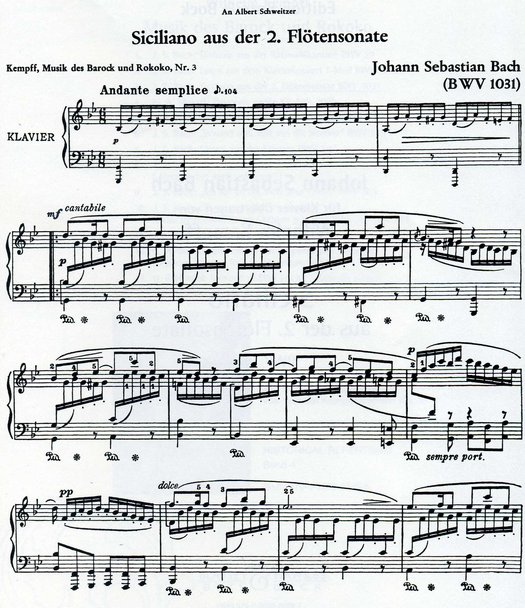

The most often played of Kempff’s Bach transcriptions is the gentle and flowing second movement from the Bach Flute Sonata in Eb major, a siciliano, or pastoral dance in 6/8 time; it is in the related key of G minor. (There is scholarly fisticuff as to whether this is an original Bach composition; some academics suggest that this had been a more complex reworking of an earlier flute sonata by Quantz.) Kempff recorded it first in 1931, but, as though he’s on tiptoes to avoid echo on the cathedral floor, is mannered, slow and processional. His 1953 recording is nearly beautiful but not quite so, polished but a trifle too corporeal (like a serviced car purring in first gear). A 1975 LP of a collection of his Bach transcriptions is a strange delight that at times echoes like a church organ, and Bach’s Siciliano in their midst is a revery, more than slightly romanticized; it is unable to decide if it should walk or skip or jump, and has an abrupt ending, as if a train running suddenly out of diesel.

The most often played of Kempff’s Bach transcriptions is the gentle and flowing second movement from the Bach Flute Sonata in Eb major, a siciliano, or pastoral dance in 6/8 time; it is in the related key of G minor. (There is scholarly fisticuff as to whether this is an original Bach composition; some academics suggest that this had been a more complex reworking of an earlier flute sonata by Quantz.) Kempff recorded it first in 1931, but, as though he’s on tiptoes to avoid echo on the cathedral floor, is mannered, slow and processional. His 1953 recording is nearly beautiful but not quite so, polished but a trifle too corporeal (like a serviced car purring in first gear). A 1975 LP of a collection of his Bach transcriptions is a strange delight that at times echoes like a church organ, and Bach’s Siciliano in their midst is a revery, more than slightly romanticized; it is unable to decide if it should walk or skip or jump, and has an abrupt ending, as if a train running suddenly out of diesel.

Several other pianists recorded Kempff’s transcription, and should you wish to touch the hem of the garment and savour the divine, then it is Dinu Lipatti’s 1950 recording that soars. It is processional and fearless, without stutter, gently fluttering like an angel in the cathedral vaults: it whets a pang for fulfilment and excites an aftermath of wonder. Kempff’s grace becomes Lipatti’s divine gift.

And for razzamatazz tinsel, the great jazz pianist Bill Evans’ version of Bach’s piece is called simply Valse. (Ha! but to be pedantic, a siciliano has two beats each bar, although each beat is divided in three.) Bill Evans had brought discernment to jazz piano; he was the pianist’s pianist with an ethereal touch and weighted vision. His 1966 trio’s recording with a symphony orchestra is more lambasted than praised by the jazz posh; it is held to be musical nylon or half-heartedly third stream. Claus Ogerman’s arrangements are inventive, often beautiful and haunting; they allow the Evans trio to float above the mawkish string orchestra rather than sink into its saccharin. Evans himself, his own harshest critic, approved of this album. And so do I.