Malcolm Saville’s Yard Broom

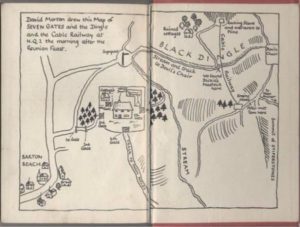

MALCOLM SAVILLE was born in Hastings in 1901 and educated there. His first job was as a clerk with the Oxford University Press, and the rest of his working life was spent in publishing. At various times he edited journals (My Garden magazine in the late 1940s, Sunny Stories in the late 1950s). He was a devout Christian, and this aspect to his life found its way on to the written page; his lifetime passions are redolent of the childhood interests of his time – rambling, natural history and cricket; he is the personification of wholesomeness – outdoor pursuit, bike rides, puncture kits, camp fires, fizzy pop if a good boy, crisps with a separate twist of salt in the packet, Sunday school table tennis, hobbies and respect for elders and betters. He was an ornamental one-nation Conservative by instinct and like so many of his generation he dusted his political views as though they were trinkets on a sideboard, yet he was liberal enough to vote for the yard broom of Labour in the 1945 General Election; this in a way sums up his writing, for he was in so many ways a yard broom rather than a duster, an expansive yoga sweep rather than the minuscule gesturing of Pilates. He had a happy marriage and four children; at the start of the war in 1939 they were evacuated to Shropshire whilst he kept the home fires burning in Hertfordshire, and their absence was the catalyst for his writing. He kept in touch by writing a book, Mystery at Witchend, set in the area where the children were staying, and based on his memories of an earlier visit in 1936. As it was written he sent each chapter for them to read. It was converted to a Children’s Hour radio play in 1943, and he wrote nineteen more in the series, known as the Lone Pine Club books. In the mid-1950s he moved to the Sussex Downs which, along with the Sussex town of Rye, feature in many of his stories also. His stories nearly always have real geographical settings, like Arthur Ransome, and usually involve a group of children having an adventure and perhaps solving a mystery. He wrote also books on nature and the English countryside.

MALCOLM SAVILLE was born in Hastings in 1901 and educated there. His first job was as a clerk with the Oxford University Press, and the rest of his working life was spent in publishing. At various times he edited journals (My Garden magazine in the late 1940s, Sunny Stories in the late 1950s). He was a devout Christian, and this aspect to his life found its way on to the written page; his lifetime passions are redolent of the childhood interests of his time – rambling, natural history and cricket; he is the personification of wholesomeness – outdoor pursuit, bike rides, puncture kits, camp fires, fizzy pop if a good boy, crisps with a separate twist of salt in the packet, Sunday school table tennis, hobbies and respect for elders and betters. He was an ornamental one-nation Conservative by instinct and like so many of his generation he dusted his political views as though they were trinkets on a sideboard, yet he was liberal enough to vote for the yard broom of Labour in the 1945 General Election; this in a way sums up his writing, for he was in so many ways a yard broom rather than a duster, an expansive yoga sweep rather than the minuscule gesturing of Pilates. He had a happy marriage and four children; at the start of the war in 1939 they were evacuated to Shropshire whilst he kept the home fires burning in Hertfordshire, and their absence was the catalyst for his writing. He kept in touch by writing a book, Mystery at Witchend, set in the area where the children were staying, and based on his memories of an earlier visit in 1936. As it was written he sent each chapter for them to read. It was converted to a Children’s Hour radio play in 1943, and he wrote nineteen more in the series, known as the Lone Pine Club books. In the mid-1950s he moved to the Sussex Downs which, along with the Sussex town of Rye, feature in many of his stories also. His stories nearly always have real geographical settings, like Arthur Ransome, and usually involve a group of children having an adventure and perhaps solving a mystery. He wrote also books on nature and the English countryside.

They are perhaps too light-hearted in their aspect to hold their own with a digital generation; there may be best suited to being housed in a chest in the attic alongside the nostalgia of butterfly nets, Howzat cricket games, jigsaws and Ludo; there is no hint of a light sabre and certainly no car chase or karate. But their expansiveness is what appeals to me: they inhabit large landscape and not an  enclosed, miniature world; Saville sets his plots in real life rather than a construct, fantastical or otherwise (Blyton’s stories were set in boarding schools or were Noddy or goblin escapades, Denys Watkins-Pitchford’s are anthropomorphic). Parents in Blyton’s novels are distant figures, almost statuesque, and for Richmal Crompton they are romantically removed, pilloried and cartoon like in their action and talk, and plots evolve around them rather than with them. In many ways he was the antithesis of Enid Blyton’s world, which was set as a museum piece or as a tableau in a school play. His plots were organic rather than derived from the film script settings of Blyton, and his characters roamed free and were not so stereotypical of the good child. Blyton’s characters were scouts and guides by rote, there was never much free fall, and not much even a whisper or suggestion that a snog was on the cards, no bike sheds behind which one stole a fag, no mucky magazine to be found in the housing estate hedgerow, no housing estates even; if one wished to be unkind then Blyton’s children might easily have been inculcated in the Hitler Youth, they are regimented and so wooden. There is something less prescriptive about Saville’s young heroines and heroes, and the two Lone Piners in the closing book even became engaged. Blyton was the literary dominatrix of her time, and, as if to characterize their intrinsic difference, when Saville assumed the editorship of Sunny Stories from here in 1956, Blyton set up her own rival magazine. There is also, in spite of the wholesome, Edenesque world he cherished, a realism that was not present in, say, the novels of Captain W E Johns, who managed to edit the magazine Popular Flying at the same time as pursuing a literary life and it is difficult not to see the join between these two worlds. Biggles was the antidote to his own bungling and inappropriate misadventure (Johns was a man who wrote off three planes in three days due to engine failure – crashing into the sea, the sand, and through a fellow officer’s back door, and, later in his Royal Air Force career, was caught in fog and narrowly escaped flying into a cliff; also he shot his own propeller off by accident twice with his ‘synchronised’ forward-mounted machine-gun; and as a recruiting officer he rejected T E Lawrence, the 1920s version of turning away the Beatles from a recording contract); Biggles was a construct, a superhero of the 1930s and 1940s and almost as unbelievable as the superheroes of the Marvel comics and latter-day Hollywood yarns.

enclosed, miniature world; Saville sets his plots in real life rather than a construct, fantastical or otherwise (Blyton’s stories were set in boarding schools or were Noddy or goblin escapades, Denys Watkins-Pitchford’s are anthropomorphic). Parents in Blyton’s novels are distant figures, almost statuesque, and for Richmal Crompton they are romantically removed, pilloried and cartoon like in their action and talk, and plots evolve around them rather than with them. In many ways he was the antithesis of Enid Blyton’s world, which was set as a museum piece or as a tableau in a school play. His plots were organic rather than derived from the film script settings of Blyton, and his characters roamed free and were not so stereotypical of the good child. Blyton’s characters were scouts and guides by rote, there was never much free fall, and not much even a whisper or suggestion that a snog was on the cards, no bike sheds behind which one stole a fag, no mucky magazine to be found in the housing estate hedgerow, no housing estates even; if one wished to be unkind then Blyton’s children might easily have been inculcated in the Hitler Youth, they are regimented and so wooden. There is something less prescriptive about Saville’s young heroines and heroes, and the two Lone Piners in the closing book even became engaged. Blyton was the literary dominatrix of her time, and, as if to characterize their intrinsic difference, when Saville assumed the editorship of Sunny Stories from here in 1956, Blyton set up her own rival magazine. There is also, in spite of the wholesome, Edenesque world he cherished, a realism that was not present in, say, the novels of Captain W E Johns, who managed to edit the magazine Popular Flying at the same time as pursuing a literary life and it is difficult not to see the join between these two worlds. Biggles was the antidote to his own bungling and inappropriate misadventure (Johns was a man who wrote off three planes in three days due to engine failure – crashing into the sea, the sand, and through a fellow officer’s back door, and, later in his Royal Air Force career, was caught in fog and narrowly escaped flying into a cliff; also he shot his own propeller off by accident twice with his ‘synchronised’ forward-mounted machine-gun; and as a recruiting officer he rejected T E Lawrence, the 1920s version of turning away the Beatles from a recording contract); Biggles was a construct, a superhero of the 1930s and 1940s and almost as unbelievable as the superheroes of the Marvel comics and latter-day Hollywood yarns.

Saville wrote 87 children’s books, and gained a weighty reputation in his own lifetime. His books, whilst always collected second-hand, have fallen mostly out of favour since the 1960s. They are fabulously creative, are extremely well-plotted adventure stories, and do not deserve neglect; there is a Malcolm Saville Society, anxious to preserve his heritage. Malcolm Saville died in 1982.