A One-Night Stand with Erroll Garner

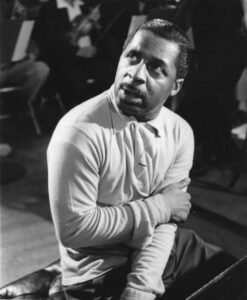

MY EYES ARE THROWN to the heavens with wonderment at the playing of Erroll Garner. When I hear him play it is as though the myriad threads of jazz history, its various twists and turns through a century of restless invention, can be distilled to one moment of definition: Erroll Garner seated on a piano stool. Not that this was a straightforward or ergonomic posture. He would be sat on a large pile of telephone directories to compensate for his short stature (Garner was only 5’2″); that he was otherwise unable to address the piano with ease was a crowd-pleasing act of mythology. Perched precariously and looking guiltily askance from his eyrie, the thousand childish faces and glottal grunts of Erroll Garner would be launched, each contorted with a nervous sense of inhibition, as though he were a child broken free from supervision but missing his playpen of restraint. Goofy in aspect, fidgety, agitated, turning ceaselessly to the crowd and impatient for their approval, Garner would nosedive from the expected, skinny-dip, belly-flop, splash like an elephant in shallow water untrammelled, drip beads of sweat in the spotlight, always a twinkle in his eye and replete with joy. Bass and drums were placed in view, not the usual jazz footprint, so that he could turn to them for comfort perhaps, to steady his own nervous enthusiasm and to keep them included. Together they made a steady four-to-the-beat, follow me to the coda essay, an improvised drill that was replayed improbably night after night in a concert hall, a club, a television studio or recording booth. In performance his body sighs visibly with pleasure, for this is the life.

MY EYES ARE THROWN to the heavens with wonderment at the playing of Erroll Garner. When I hear him play it is as though the myriad threads of jazz history, its various twists and turns through a century of restless invention, can be distilled to one moment of definition: Erroll Garner seated on a piano stool. Not that this was a straightforward or ergonomic posture. He would be sat on a large pile of telephone directories to compensate for his short stature (Garner was only 5’2″); that he was otherwise unable to address the piano with ease was a crowd-pleasing act of mythology. Perched precariously and looking guiltily askance from his eyrie, the thousand childish faces and glottal grunts of Erroll Garner would be launched, each contorted with a nervous sense of inhibition, as though he were a child broken free from supervision but missing his playpen of restraint. Goofy in aspect, fidgety, agitated, turning ceaselessly to the crowd and impatient for their approval, Garner would nosedive from the expected, skinny-dip, belly-flop, splash like an elephant in shallow water untrammelled, drip beads of sweat in the spotlight, always a twinkle in his eye and replete with joy. Bass and drums were placed in view, not the usual jazz footprint, so that he could turn to them for comfort perhaps, to steady his own nervous enthusiasm and to keep them included. Together they made a steady four-to-the-beat, follow me to the coda essay, an improvised drill that was replayed improbably night after night in a concert hall, a club, a television studio or recording booth. In performance his body sighs visibly with pleasure, for this is the life.

Garner’s crowning achievement was his exquisite use of time. In jazz the possession of swing is nine tenths of the law, and Garner’s swing was natural and faultless. The left hand chugs on the beat, chugs relentless as a steam train, its pistons drawing breath as if stoked with a wallop – an occasional and last beat of the bar lunge ahead of itself to unnerve the train, the prospect of derailment and disaster; as it winds up the track the music has no time to cast a satisfied look over its shoulder for it is already full steam ahead. He could be as delicate as a sidewinder slipping in the desert sun or as intricate as an eel tricking its way from its pit. The nonchalant, breezy and rapid right-hand chords, effortlessly realised, sparkle and dance; they might invoke onomatopoeic words such as crunch and crash, are delicious and clatter yet have grace. But their offbeat timing is the thing. Either momentarily delayed or in anticipation of the beat, they disorientate our ears with a dizzy disruption of a steady measure. The intermittent, contrasting and playfully pecked one note lines (delivered with no forethought of fingering) are leisurely or urgent, lengthy or curtailed, offered with skittish rapture as another (probably better) idea scuttles across his keyboard. This two-handed momentum leaves you bewildered, gently concussed as though smitten about the head with a feather boa: outrageous. There you have it in its entirety: a style so compact, so at one and so at ease with its performer, it is in equal measure heartbreaking, tender, swank, rumbustious, so much else; sometimes it is all of these in rapid fire succession and so much else.

There is not a lot to say about Erroll Garner the man. He was born in Pittsburgh, possibly in 1921 or it might have been two years after. We know that he played the piano from three years old and that from an early age he could play back by ear whole passages he had just heard for the first time. It is said that after attending a concert by Emil Gilels, the bear of Russian keyboard virtuosi, he rushed back to his room to play back to himself from memory the passages that had affected him most. Music came easy and he couldn’t read a score; indeed his home town’s music union denied him membership for many years on those grounds.

Garner moved to New York in 1944 and recorded with Charlie Parker in 1947. This was

Garner moved to New York in 1944 and recorded with Charlie Parker in 1947. This was

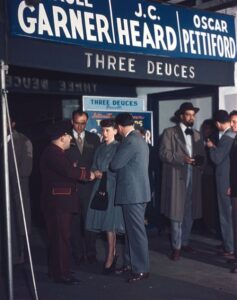

bebop by rote. Strident, bass acciaccatura notes on the dominant, stabbed chords and other keyboard tics that had been acquired for this studio date, copied presumably from Bud Powell. His solo lines coruscate, but when accompanying Parker, Garner is wooden and like a fish out of water. This is the only time on record that Garner engaged with mainstream jazz, and this walk-on part is completed by an overused stock photo of Garner’s name high on the billboard of the Three Deuces in 52nd Street, Manhattan’s bebop boulevard that housed many of the vibrant clubs of the day. Bebop, in keyboard parlance, did not embrace the full seven octaves and was weighted to the pianist’s right hand, whereas Garner ran up and down the keyboard with two full-fists. But the truth is that he was always a musical loner and not inclined to cut his musical cloth to accommodate others. By the early 1950s his musical voice and the manner of his playing is so secure and comfortable in its individuality that even today he remains a backwater of the jazz idiom. Garner is the church brass from which no rubbing should be made; any rubbing would be seen immediately for what it is – grand theft.

He performed solo in earlier days and he gave way to an extra percussionist occasionally in his later years as he aped popular Latin sounds and chopped up his left-hand rhythms, but the trio was his format of choice and throughout his career he stayed faithful to it. The Erroll Garner Trio was feted worldwide and was a popular guest on many prime-time TV shows (Johnny Carson a massive fan, so too Mike Douglas). He became one of the most marketable names in jazz, so marketable that it fell outside the remit of the diehard fan. Garner’s album Concert By The Sea, a 1955 live recording made on the hoof and initially for private consumption, was released by Columbia Records in simulated stereo and was a hefty commercial success. His composition Misty was a worldwide hit (Johnny Mathis’ rendition alone sold over two million copies); it was also the prompt for the Clint Eastwood film Play Misty For Me. There can be little doubt that when Garner’s estate was considerable, but what Garner did with his fortune is not clear for no sense of his biography can be traced on Google. Seemingly he was a reluctant interviewee, but the one example I can find is conversational and intelligent. A lifetime of chain smoking and chronic emphysema caused his early death, I think a fatal heart attack in a lift.

If the man is a riddle lost in his time, the piano playing is with us still. It is still daring and louche, off-kilter and breathtaking with its cheek and élan. His homespun technique could interpret any sound that he could care to hear in his imagination, and the sonorities held in his fingertips could match those of a big band. Peculiarly he exhibited inconsistent aesthetic taste. This makes me fond of him even more (if rather keen to skip LP tracks) for it hints at stubbornness and an idle disposition, as though he didn’t have the attention to do his homework properly and didn’t care that much for the consequence. Perhaps he had no ambition other than to do what he found easy; cumulatively, over the length of a career, the scope of his musical world can be seen as limited.

One of his trademarks was to bolt on a random introduction to a piece, a disjointed burlesque or gibberish that would depict, say, two cats fighting in a phone box, and seldom did the introduction relate to the song’s content. This might tease his audience (and his trio) but was naff and exhibitionist. He was known for his ballad playing, yet often all I hear is rhapsodic tinsel, indulgent and gushing left-hand smooch with an excess of pedal; Liberace could have done worse but few others in the history of popular piano. Yet for all the musical candyfloss, his cheesy grin and saccharine musical tooth, he imparted joy. Erroll Garner’s playing was not just sweet but bold and precise, for he wished to communicate and, if only for passing moments, he bolted urbanity to the commonplace, hyperbole to the throwaway. Above all else he wanted to kid you that he was not just heartfelt but profound. He was a one-night stand that sought to offer tenderness and affection, and I love him for that.

early Erroll Garner, recorded 1947, Undecided

Erroll Garner in performance on French TV, May 1