Neophyte Days, Troglodyte Ways

“When I worked in a second-hand bookshop… the thing that chiefly struck me was the rarity of really bookish people.” – George Orwell, Bookshop Memories

MY WORLD OF ambition: the rickety bus, ramshackle and haphazard. It lolloped into Oxford centre to deliver me, my cases of second-hand books and my short-trouser schemes. Forty-two years ago, primed with enough ammunition to set the course of my life with bibliophilic dynamite. A match struck that might burn enough to make money from selling books. I had left the University here and stumbled into bookselling rather like cattle might tumble backwards into a cattle grid. It happened by accident when a post-university plan to work in Israel fell through. (Israel had decided to invade one of their neighbours, and am not able to recall which one; take your pick.)

There is no call for my book laden bus travel now, but the 280 bus from Aylesbury to Oxford still runs, sometimes I think with the same driver as in my youth. Each journey makes more profit than I’ve done all my life. It is regular but always late. It sets off each half-hour, thirty miles or so each way of meander and gallop. The first village stop is, as then, Stone. A miniature and hidden pond is its pivotal point around which the bus will hurl itself: centrifugal force meets Miss Read. The ghosts of Stone’s past whisper still in the breeze; its large psychiatric hospital, long ago demolished, was as crucial to the village as the purported, no doubt imaginary purpose of its name – a stone set at the point furthest from the sea anywhere in England. The bus here lets on retired farmhands. The journey is temporarily a pensioner’s jaunt to buy their meat, cheese and vegetable from Thame; wedding dresses and double beds are bought at Oxford once each marriage. Next stop is Haddenham, a melee of school playing fields and planning applications. Its inhabitants are seated in their houses, each reading the minutes for the last PTA or Neighbourhood Watch meeting; it is very demure, very parish council. Then Thame, where a public house can be spied on every corner. The town boasts enough butcher’s shops to merit a quarry of whetted stone just to sharpen the cleavers. The tidy thatched roofs rest on the High Street buildings like tin hats on soldiers returning from the Great War; interest in the cause is long lost, despair visible in their eyes. Despair can be seen, too, in the bunches of straw and sedge for this town may be the last bastion of old England, with its fruit markets decorating town squares weekly, its church fetes and paper boys. The last detour to Wheatley is unwelcome and the eager appetite for Oxford that has been fed by the bumpy twists of this journey is stalled with irritation.

At last, through its parade of shops and down Headington’s hill, over Magdalen Bridge and then across the Plain. The bus saunters along the High for me to alight opposite All Soul’s. A gentle walk awaits: my feet follow the footnote trail through the Radcliffe Square and the Bodleian Quadrangle, past the Sheldonian and through the Clarendon Building. To Blackwell’s, the bookshop of the golden mean, replete and fat with its history and its learning.

THROUGH LIBRARIES, THROUGH generous aunts and uncles, through the treasure of the book token and my own pocket money, I have learnt to love books: all that they stand for, all that they are. Perfect ergonomic technology with generations of thought invested in a simple, weighted and streamlined mechanic form. Throughout my life I have had an instinctive inclination, an urge even, to hang on to as many of those precious objects that came my way as possible and even to add to that number. As an eager six-year-old boy, I was taken each Saturday morning to W H Smith’s in Aylesbury High Street. One shilling and threepence burnt a hole in my pocket. This was my pocket money, its total derived from parental cunning rather than accident, for its aggregate, once my grandmother had chipped in, was the exact price of a Ladybird history book. This ritualistic, weekly purchase meant I had bought all of this series within a year. I was immensely proud of my horde and I read them tirelessly. The story of Robert the Bruce was my favourite, but I loved all epic, historic tales of bravery and foolhardiness: King Arthur, George and the dragon, Nelson spying the French fleet with his blind eye, poor Scott of the Antarctic, Robin Hood and Little John especially.

In earlier times, my Robin Hood story book collection grew and was read out loud to me. It was replaced by proactive colouring books. Then I struggled solo with my own reading book (all I remember of this edition was that it was very large and satisfyingly thick and had each of Robin’s merry men sketched on its endpapers). Eventually I graduated to the gallant retelling by Richard Lancelyn Green, and even now I await Kevin Crossley-Holland’s version, but sadly he is reluctant.

Every step of my juvenile path, as I took on a different reading shape and as my life experience and palate gathered pace and taste, I was determined to prune some books from my shelves as they bulged, at least those whose presence had outlived their use; I may even have become ashamed of them. My literary culling season each year was brief and could be merciless. It was one of the yardsticks of my youthful, yearly calendar, which consisted of my birthday, Christmas, Easter eggs, football Cup Final day, summer holidays with my cousins, Bonfire night, the throwing out of books. Paddington Bear was the bee’s knee when I was six, but by the time I was eight Paddington was an embarrassment, his destiny was to be jumble. He had been replaced by the George Best Annual and Paddy Crerand’s autobiography (the Glaswegian Manchester United midfield maestro, hard as nails, the true mastermind of Matt Busby’s European Cup winning team of 1968). C S Lewis and, reluctantly, J R R Tolkien (neither were known to have been decent at football), The Silver Sword, Stig of the Dump, The Otterbury Incident, and, my favourite of all,  Bill Naughton’s The Goalkeeper’s Revenge came and went out of fashion, but maintained their space on my bookshelves because I was proud of them; a lot of Henry Treece and Malcolm Saville in-between. Only in my pubescent teen years, rife with masturbation and rugby, did Treece and Saville become lacklustre; they represented worlds I no longer wished to imagine. They had no lustful intent either, and these volumes, like my Captain W E Johns’ Biggles, Richmal Crompton’s William, were to be hidden from public view (rather like the smutty Confessions Of A… series of books that replaced them secretly!). I got to sell them on to Weatherhead’s Bookshop in Aylesbury town, its place in Kingsbury’s square (which was a triangle and contained the bus stops and the Regency cafe with its wallpaper of flying ducks). This was my first taste of making money from books and it must have been like the lion’s first kill: I liked the taste of bookselling blood. I reinvested the booty, buying from the shop’s cheap racks at its frontage. Here I could buy for five pence each my paperback flavour of each new month: John Creasey, Edgar Wallace, Erle Stanley Gardner (who is still my favourite detective tipple). Ian Fleming’s James Bond became my thriller muse for a while, in spite of Roger Moore’s parodical naffness on the big screen at the time; Alistair MacLean, Desmond Bagley and all those other Fontana adventure writers who never quite hit the mark for me, although I gave each of them a chance. Ultimately all were vanquished by the more sedate writing of J B Priestley – The Shapes of Sleep a cracking book, I recall – and especially Somerset Maugham: Rosie’s breasts wobbled off the pages of Cakes and Ale each night-time if I let them. I always did.

Bill Naughton’s The Goalkeeper’s Revenge came and went out of fashion, but maintained their space on my bookshelves because I was proud of them; a lot of Henry Treece and Malcolm Saville in-between. Only in my pubescent teen years, rife with masturbation and rugby, did Treece and Saville become lacklustre; they represented worlds I no longer wished to imagine. They had no lustful intent either, and these volumes, like my Captain W E Johns’ Biggles, Richmal Crompton’s William, were to be hidden from public view (rather like the smutty Confessions Of A… series of books that replaced them secretly!). I got to sell them on to Weatherhead’s Bookshop in Aylesbury town, its place in Kingsbury’s square (which was a triangle and contained the bus stops and the Regency cafe with its wallpaper of flying ducks). This was my first taste of making money from books and it must have been like the lion’s first kill: I liked the taste of bookselling blood. I reinvested the booty, buying from the shop’s cheap racks at its frontage. Here I could buy for five pence each my paperback flavour of each new month: John Creasey, Edgar Wallace, Erle Stanley Gardner (who is still my favourite detective tipple). Ian Fleming’s James Bond became my thriller muse for a while, in spite of Roger Moore’s parodical naffness on the big screen at the time; Alistair MacLean, Desmond Bagley and all those other Fontana adventure writers who never quite hit the mark for me, although I gave each of them a chance. Ultimately all were vanquished by the more sedate writing of J B Priestley – The Shapes of Sleep a cracking book, I recall – and especially Somerset Maugham: Rosie’s breasts wobbled off the pages of Cakes and Ale each night-time if I let them. I always did.

It was only in this more percipient and subdued style of “grown-up” writing that I could locate the consumptive hero figures who appealed to my growing teenage sense of existential angst. By turn, Dickens’ Paul Dombey and other saccharine child-heroes, next the mild-mannered, pre-socialist consumptive found in Henry James, had become too much like my Aunty Lily and Uncle Ted coming to tea, when everyone was on their best behaviour, drank tea from a cup and saucer and spoke of jigsaw puzzles. It was only when I went European that I discovered literary consumption that truly ached. Indeed, it had matured to the far more dramatic cholera. I was by then a bit too old to play out an imaginative death scene if I slumped in the deckchair of my back garden, but already I knew of pointless longing and heartache, for I read Death in Venice several times in the wake of Dirk Bogarde’s film portrayal of Aschenbach, who died slumped in a deck chair on the beach. Thomas Mann’s book opened a whole new world of writing to which I could attach my own longing and heartache in my later teenage years.

Everything European was dramatic. They had wars and revolution; all England could offer was two weeks of Wimbledon and licorice. There was an intensity in European despair and you could see that etched onto Edward Heath’s face as he led us into the Common Market. My world expanded, as books like Céline’s Journey to the End of the Night left an overwhelming and devastating impression. Moreover the characters in European novels acted cool (Simenon’s Maigret was the perfect role model) and had cool names: Tadzio, Raskolnikov, Meursault. My sixth form years were the high tide of my intellectual coolness, a self-conscious period of my life when I would overdose with acne cream, attempt to shave, drink coffee in the delicatessen next door to Weatherhead’s in Kingsbury – the bookshop solely responsible for my reading habits at this point, whose slow turning stock defined my literary parameters. And whilst drinking coffee, my friends and I made patterns with the double cream that we poured into our cups via an upturned teaspoon; I was sure that Sartre and Camus did this on the Rive Guache after the war.

This adolescent and ambitious white noise was extremely judgmental, tense and considered. All of a sudden it really mattered to me which books and which writers studded my bookshelves. They had to earn their place, I had to be proud to have them there. The black liveried Penguin Classics and their light green Modern Classics variant mirrored especially my precocious, intellectual ego. I handled these books with great care and forbade even the hint of a crease on their spines. Sadly, I kept them even in alphabetical order. Freud would have declared me regressed to my anal stage of development, I’m sure, but I see now how the annual, sequential ransacking and resurrection of my book collection that I wrote of earlier was more than a rite of passage, and more than the measurement that tracked the growing length of my stubble. They were custodial clues about the true nature of a personal library: it is not just dogs that resemble their owners, books also.

I WAS RUNNING books, then, in 1982 from a nearby market town to the academic, provincial avatar that is Oxford, to sell them on for what I regarded to be a great profit. These were the last knockings of days when the ‘runner’ existed: his or her (in fact always his) job was to sell books from one shop to another. The mainstay of this alarmingly masculine second-hand book trade was incestuous. Most provincial booksellers opened their doors each day to buyers from city shops, often specialist dealers, and to these runners, the trade’s middle men who generally had neither a shop nor any stock in hand. What made its way onto bookshop shelves was priced often according to what this passing trade would pay (acknowledging their ten percent trade discount). Any book might be passed from bookseller to bookseller several times before it was sold finally to the end user, its bona fide customer. Before the age of the internet there was a sliding scale of cash offered by booksellers for books, the rate dependent on their place in this economic firmament; that place was determined by their geography, their customer base, their specialism and, importantly, the bookseller’s own interest and intent. (If you find a remarkable bargain in a shop, it may just be that the bookseller does not care for it or wants shot of it!) Some booksellers might never see a legitimate end user of any book they sold, preferring to sell to the trade only. So divorced might these booksellers be from the public, that many old-time booksellers cared little for their non-trade customers and didn’t mind showing it. This commercial book world worked because all of its components knew their rung on this hierarchical trade ladder.

Whilst the trade fraternity policed itself moderately well (dishonest dealers selling within the trade could be shunned out of business), second-hand bookselling had a reputation historically for being dishonest at times, although I have found it always to be remarkably fair. Just as there are fraudsters and pickpockets in real life, so too the book trade had occasionally its drifters, chancers and no-hopers. Many of those who remembered these days of the wild west – of cowboys and customers – tended to pride themselves on their own ignorance of books and their ostensible purpose (which is the words within them, designed to be read in order, usually). Books were sold in the book trade so often as though they were carcasses of meat. Some of the traders whose careers had started before the Second World War had sold their books originally from a barrow. Fred Bason’s diaries (four volumes, his vantage point offered fabulous if colloquial insight into so much more than bookselling) describe how the best price for each book was obtained. Each day started by selling all books at a certain (high) price. As the day progressed, the books’ prices lessened on each hour. Customers would return at the designated point each day when the book they desired reached its appropriate value, at least for them: open market value at its most unalloyed.

In my neophyte days I got to know Peter Eaton. He was almost too respectable, a criminal manqué, certainly a doyen, almost unrivalled, of second-hand bookselling history. He had walked from Lancashire to London when a young man, sold books at first from a barrow on the Portobello Road, opened his first shop in Kensington High Street; his last London shop, stylish with potted plants, was in Holland Park. He had also The Lilies at Weedon, a huge mansion three miles from Aylesbury; here he stored his reserve stock which had previously been strewn like confetti all over London.

The grand house might have been home to Benes and the Czechoslovak or some such displaced government during the Second World War War, I think; it had certainly been a wartime hospital. Eaton had put its boundaries on the map in my childhood when he was conducting a voifcerous, parochial vendetta against the local hunt. Weedon was still the secure, pastoral preserve of the Shire communities. Frank Weatherhead, the second-generation owner of the Aylesbury bookshop, had recommended The Lilies, a huge house, to Eaton; the handshake agreement was that he would not poach on the local Weatherhead business. Although The Lilies was intended to be Eaton’s storeroom and country retreat, it became in effect the largest bookshop in the country. One of his trade specialism was ransacking public libraries and buying their cast-off stock at knock-down price; often this comprised much sought-after academic texts on the cheap. Some of my Oxford tutors would group together and motor to The Lilies, though an appointment was advisable always. When there they would be delighted to be summoned by bell to the drawing room for mid-afternoon tea, served on bone china, with digestive biscuits; after such recreational, light repast, they would resume their addiction and hunt through the twenty or so capacious rooms, each flooded with stock. Also the huge basement where prices could often be rock bottom. They would leave with a car boot full of books.

Peter Eaton was a fascinating man, a biographer of Marie Stopes, friend to many literary glitterati, confidant to the bookish Michael Foot, and a devotee of the Powys brothers. John Cowper’s death mask was on display on the top floor where Eaton had a tag, rag and bobtail of a museum, its exhibits as idiosyncratic as its curator; the highlights were King George VI’s ration book and the “clock that belonged to the people who put the engine in the boat Shelley drowned in.” Significant and collectible works of art that elsewhere might have missed the bullseye hung like graffiti on the stairs and landings. Eaton, as I remember him, always with a country bumpkin chequered shirt and squinting quizzically, waving his glasses aloft, was scruffy and misanthropic, the distillation of the bookseller to its purest form. His disdain for customers was all but legendary. Yet he was a bluster and bluff gentleman, decorously civil. I watched him once barter with Frank Weatherhead for two suitcases full to the brim with first edition Powys brothers, all in good condition with their dust jackets; decades of negotiating skill and wheedling guaranteed him the best price. His wife, Margaret, guarded the fort in his later days, when he concerned himself more with his radical obsessions: all booksellers in their purest form are left wing, even Communist if allowed to set like jelly in the fridge. He would speak openly of his nefarious bookselling past, also with jaded scorn of the new breed of educated, parvenu bookseller who held their job to be a calling.

I worked in Aylesbury at Weatherhead’s Bookshop for a few years after university. This was the most wonderful of experiences. I loved it so much that within six months I had gone to see a bank manager, dressed disrespectfully in a t-shirt, and asked how I could borrow money to start my own shop. Frank Weatherhead, by then in his late seventies, was still involved casually two days each week; he was grumpy and tended to communicate as poorly as a medium with no Ouija board. Nick, his son, was now in charge. He was inhibited by his father’s presence perhaps, but was kind, artistically debonair, didn’t care to work too hard, and was a bit idealistic. He sat in his office computer programming (in its early pirate days) and plotting his escape from the book trade. Eventually he achieved this by relocating to Cape Wrath where he started a hotel for birdwatchers (the feathered kind), although after too many frozen water pipes he conceded defeat there and fell back to another bookshop in Bodmin.

I worked in Aylesbury at Weatherhead’s Bookshop for a few years after university. This was the most wonderful of experiences. I loved it so much that within six months I had gone to see a bank manager, dressed disrespectfully in a t-shirt, and asked how I could borrow money to start my own shop. Frank Weatherhead, by then in his late seventies, was still involved casually two days each week; he was grumpy and tended to communicate as poorly as a medium with no Ouija board. Nick, his son, was now in charge. He was inhibited by his father’s presence perhaps, but was kind, artistically debonair, didn’t care to work too hard, and was a bit idealistic. He sat in his office computer programming (in its early pirate days) and plotting his escape from the book trade. Eventually he achieved this by relocating to Cape Wrath where he started a hotel for birdwatchers (the feathered kind), although after too many frozen water pipes he conceded defeat there and fell back to another bookshop in Bodmin.

This Aylesbury shop had opened originally in Folkestone after the First World War; it moved to Buckinghamshire at the beginning of the Second World War to escape the bombing. The original site in Buckingham Street was quite small, but after Frank returned from the front with a loyal friend (Basil Shaw worked in the shop until shortly before the family sold the business in 1985, a remarkable man who, even when nearly 80, could be found hanging out of a first floor sash window by one hand, the other rethreading its cord), the firm swapped its smaller building for a much larger premise round the corner in Kingsbury. This site had been a hat shop. Much of its original first floor shelving was kept, though it was far too deep and tall for books but jolly convenient for visitors with high hats even forty years after the Weatherhead family took possession of the shop, when I was working there.

Aylesbury is a small, market town. It numbered only 40,000 inhabitants in the 1970s but was the magnet for a diverse, rich and essentially rural county tapestry. Its charm had been interrupted by a brutalist vision of concrete and desecration: its cobbled streets and claustrophobic, condensed buildings in its middle had been bulldozed by Council edict in the 1960s. Its new open air and covered markets, dropped on site in the late 1960s as though some oppidan manna from a science fiction novel, mopped up any life and character from the town; indeed its new county offices – dubbed as Pooley’s Folly, named after its architect, possibly the worst architect ever whose own house in Wendover was a miniature mush of what he did in many Buckinghamshire town centre – had risen in the 1960s like an alert boa constrictor wrapped around an edifice of transport policy makers, town planning, public health officialdom, marriage records, a library and all else. Not surprisingly the new market and its nightmare precincts served as a film set for futuristic scenes from Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, though these takes never made the final cut.

Aylesbury is a small, market town. It numbered only 40,000 inhabitants in the 1970s but was the magnet for a diverse, rich and essentially rural county tapestry. Its charm had been interrupted by a brutalist vision of concrete and desecration: its cobbled streets and claustrophobic, condensed buildings in its middle had been bulldozed by Council edict in the 1960s. Its new open air and covered markets, dropped on site in the late 1960s as though some oppidan manna from a science fiction novel, mopped up any life and character from the town; indeed its new county offices – dubbed as Pooley’s Folly, named after its architect, possibly the worst architect ever whose own house in Wendover was a miniature mush of what he did in many Buckinghamshire town centre – had risen in the 1960s like an alert boa constrictor wrapped around an edifice of transport policy makers, town planning, public health officialdom, marriage records, a library and all else. Not surprisingly the new market and its nightmare precincts served as a film set for futuristic scenes from Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, though these takes never made the final cut.

The town had been the historic focus of Britain’s print industry. Hazell, Watson & Viney was the biggest employer until Robert Maxwell massacred the company. Hazell’s was responsible single-handedly for littering household letterboxes with junk mail, the monthly Reader’s Digest magazine and the Radio Times as well as most case bound books found in bookshops. Hunt Barnard was Hazell’s more sophisticated rival in town, and a host of other print-related businesses. The town’s agricultural hinterland – it had a picturesque cattle market, cobbled and with a circular shrine where livestock was sold, visited by all animal loving children as well as farmers and auctioneers – meant that it was vibrant with mercantile modesty. It was saturated with high class independent shops, owned often by the same families for generations, as well as the hustling multiples as they hit our retail landscape and multiplied each decade. A conscientious grammar school town like this might have been expected to support easily a bookshop as well as a general stationer: W H Smith’s sold books in the High Street also. Weatherhead’s saw off its bookshop opposition: May’s in Walton Street gave up its bookselling and reverted to art material and dealing in stamps; the senior Mr. May was bitter with Frank and his family’s kingdom, it seemed, until his final days, and he wasn’t slow in broadcasting this. A branch of Claude Gill opened in Kingsbury but that lasted less than a decade. Weatherhead’s owned a sister shop in High Wycombe as well for some time. It was in every sense the county bookseller.

This shop in the Kingsbury square – an old aircraft factory was a near neighbour, also William Jowett’s the ironmonger which was started in the 1800s and was still trading then – was a red carpet for the imagination. Its mythology lives on, very much treasured by anybody my age or older; that the internet has bypassed this mythology is a great shame, for there is barely a mention of it online. Local bookshops once shaped their localities, and, had estate agents needed to sell the town, no better advert could be found for Aylesbury than this shop. Wooden floorboards, a basement that nobody had entered for decades, its back extension built precariously on its garden walls, an extensive upper floor window roof that rattled like copulating skeletons when the wind blew and which leaked in heavy rain; staff would rush round with buckets to shied the drip from the books. Its back space was built like a maze with aisles either side and cumbersome, homemade tables. It was well lit and earnestly bookish, but neither stuffy nor elitist; it displayed a wholesome interest in subjects like natural history and bird watching (the feathered kind; bookshops though are superb dating agencies for male booksellers, who by tradition are ugly and need all the help they can get). Over the years it had accumulated books from the libraries of Edgar Wallace, Bernard Shaw, Francis Chichester, many others. Chequers was close by and Prime Ministers would call in at Christmas; Edward Heath when in office held a book signing

This shop in the Kingsbury square – an old aircraft factory was a near neighbour, also William Jowett’s the ironmonger which was started in the 1800s and was still trading then – was a red carpet for the imagination. Its mythology lives on, very much treasured by anybody my age or older; that the internet has bypassed this mythology is a great shame, for there is barely a mention of it online. Local bookshops once shaped their localities, and, had estate agents needed to sell the town, no better advert could be found for Aylesbury than this shop. Wooden floorboards, a basement that nobody had entered for decades, its back extension built precariously on its garden walls, an extensive upper floor window roof that rattled like copulating skeletons when the wind blew and which leaked in heavy rain; staff would rush round with buckets to shied the drip from the books. Its back space was built like a maze with aisles either side and cumbersome, homemade tables. It was well lit and earnestly bookish, but neither stuffy nor elitist; it displayed a wholesome interest in subjects like natural history and bird watching (the feathered kind; bookshops though are superb dating agencies for male booksellers, who by tradition are ugly and need all the help they can get). Over the years it had accumulated books from the libraries of Edgar Wallace, Bernard Shaw, Francis Chichester, many others. Chequers was close by and Prime Ministers would call in at Christmas; Edward Heath when in office held a book signing  there. Most of the electorate pretended to be sailors, like Ted, vote Tory (not difficult in leafy Buckinghamshire) and be incredibly bad organists for the day (though none could pretend to be as bad as Heath, reputedly the organ scholar at Balliol). The shop was a surprisingly expansive enterprise that was a Tardis on its first (and second floor), stretching over the shop next door. It employed nearly twenty people even in its later days. Upstairs was a large room full of antiquarian stock, another room devoted to several types of catalogue sent out for mail order custom, which included much international trade; the shop’s turnover was at least doubled by library and school supply. There was a vast stock downstairs in the shop – plenty of new books but mostly second-hand, and at any one time there were typically a half-dozen trade dealers in residence, burrowing, climbing, sniffing out cheap stock as though pigs after truffle. It had also a massive warehouse at its rear. This building had been one of the town abattoirs, its hooks and chains still hung from the ceiling. An alternative store in a town house around the corner was set alight one night; many charred books lay stretchered on the top floor of the old abattoir like invalids.

there. Most of the electorate pretended to be sailors, like Ted, vote Tory (not difficult in leafy Buckinghamshire) and be incredibly bad organists for the day (though none could pretend to be as bad as Heath, reputedly the organ scholar at Balliol). The shop was a surprisingly expansive enterprise that was a Tardis on its first (and second floor), stretching over the shop next door. It employed nearly twenty people even in its later days. Upstairs was a large room full of antiquarian stock, another room devoted to several types of catalogue sent out for mail order custom, which included much international trade; the shop’s turnover was at least doubled by library and school supply. There was a vast stock downstairs in the shop – plenty of new books but mostly second-hand, and at any one time there were typically a half-dozen trade dealers in residence, burrowing, climbing, sniffing out cheap stock as though pigs after truffle. It had also a massive warehouse at its rear. This building had been one of the town abattoirs, its hooks and chains still hung from the ceiling. An alternative store in a town house around the corner was set alight one night; many charred books lay stretchered on the top floor of the old abattoir like invalids.

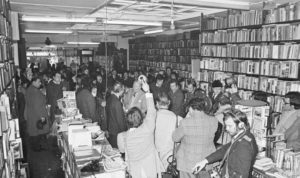

The shop was massively busy when I started to work there, especially on a Saturday when it was swamped routinely throughout the day. Books were sold as though linen – by the yard; customers would leave often with a pile an arm in length two arm lengths sometimes. My memory was that such intense book buying, especially the leisurely type, was mostly a male preserve; at times at the weekend it felt as though the shop was a playpen for the truant husband hiding from his wife who had been deposited elsewhere to shop for groceries. Books were strewn across the wooden floors, piled high everywhere, shelving often as tall as twelve foot above the floor; ladders and steps were available for those immune to vertigo or nosebleed. I witnessed the art of reverse marketing: the quickest way to sell a second-hand book was to place it in a box, place a sheet on top that said NOT FOR SALE, then push the box under a table. That was an open invitation to rummage for any customer worth his salt. Or if a customer enquired after oracular subject matter, the best way to pique their curiosity and encourage them to forage in the bookish undergrowth was to tell them that you doubted there was much of interest for them, for the archetypal dedicated book buyer was valorous, rather like a dangerous sportsman with crampons and oxygen mask to hand and willing always to abseil or pothole for his books.

On the days when Nick Weatherhead had been out buying and had returned with his van full to the brim to sell this stock was easy. Eager to cast my eye over the day’s bounty, I would volunteer to unload while Nick sat on a stool at the back of the shop, pricing his fresh stock, but books would be snapped up by customers even before he had wetted his pencil. (Incidentally, each bookseller has a distinct signature script, and very often you will see still a bookseller’s coding or hieroglyph on the endpaper denoting the date of acquisition, price paid, the library it came from, etc; later, as a bookseller local to Aylesbury, books priced by Frank Weatherhead perhaps seventy years earlier came my way from time to time.) No sooner had I laid out the freshly arrived books on the floor, or clambered a ladder to squirrel them away on a vacant shelf, when eager trade dealers swooped upon them like birds of prey in search of carrion. Booksellers resemble vultures so often.

Nick had forgotten more than he had ever known; bookselling was a second skin to him although he was the jack of the trade and never its master. Even so I had begun my service in the shop haughty and superior, sure that I knew all about books and certain that Nick sold his books regrettably cheap. After a while I saw that his sales reflex was in fact keen: he was spot on and the best bookseller I could ever imagine to work for. His instinct was for a fast turnover at a time when three or four vanloads of books stacked to the roof trim would be collected from the outer reaches of the county each week. In previous decades the library pickings had been even more prolific. After 1945, the wealthy Edwardian families had seen their inherited wealth plummet and their expenses go though the roof. This is chronicled by James Lees-Milne, is another story, but is perhaps integral part to the collapse of the importance of the book in our society. Weatherhead’s had benefited by the aristocracy’s decline and its need to fashion more affordable lifestyles (and pay off their inheritance tax). They were all keen to discard their family libraries.

OXFORD INCLUDED MORE than a few booksellers of calling in my days of university book buying, the ‘aristocrats,’ as Peter Eaton called them. Most of its bookshops were high up the bookselling ladder I have described, its customer base truly international. Yet contained within the city was a broad bookselling church of personality, resonance and outlook.

This number included knowledgeable, nouveau starlets like Peter Hill, my contemporary at university, and Marcus Niner, whose shared modest book hovel was in the High and opened a few years after I left college. They were always keen to buy but never seen to sell (their white rabbit custom was kept hidden up their sleeve), especially keen on polar travel and ‘topography’ – this a term of gravitas. (Later the less ornate ‘local interest’ came to be used, a nomenclature that signified the dumbing down of both bookselling and society.) The pair was as safe as Arsenal’s flat line of defence, a dream team of the trade. Peter was hunter-gatherer, his peripatetic ways kept him on the road to scour the country for stock, to return with his trophy like a cat with a rat; Marcus was the housewife who hoovered and dusted and kept the home fire burning. Also the Classics Bookshop at the corner of the Turl, a nicely proportioned bookshop with a balustrade above its ground floor, very theatrical if not quite authentically Shakespearean, but it held rows and rows of Loeb classics racked like deck chairs on a sunny day at the seaside. You might imagine only ink and quill were used here, never a Biro or anything too modern; blotting paper and cake might be taken with afternoon tea.

Other proper antiquarian bookshops were spread over the Turl and other pedestrian backwaters, as shunned as cemeteries, disturbed only by those with interests as alabaster and derelict as death. Their owners, who habitually wore white gloves to avoid inflicting damage upon their relics and corpses, were as humdrum as incunabulum; they would turn the pages of books delicately and perversely as though they were fondling the Holy Ghost. No doubt they recited bibliographies instead of prayers at bookshop evensong.

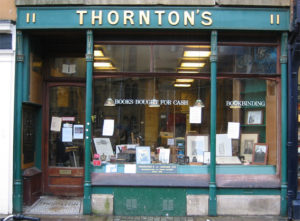

The bookselling war horse that was Thornton’s was positioned like a trade gendarme in the centre of the Broad; for those in its orbit, it set high standards. By this time it was in its dotage, old man Thornton similarly (he it was dozing at its back desk, I was told), and was recklessly tumbledown. Various tributaries flowed from its cashpoint delta, arranged as defiantly as a musical coda with no resolution as its cash desk notched up sales after sale. A rostrum of rooms, big or small, that had as many books laid on the floor in front of the book shelves as upon them, were connected by staircases, resting spaces to recover your breath, and each similarly littered with nooks and crannies, some so tight that you could barely breathe when inside them. It was a many tiered, multi-volume scrum that defied health and safety yet always made perfect sense to the true bibliophile. He or she needed no compass to steer a course from reportage to belles lettres, through the literary criticism, stopping off at French modernist poetry, though never finding a fire exit along the way – the shop’s undoing in the end for it was closed. The shop may have been less exciting than I describe, but I fancy it may have taken Stanley longer to find Livingstone inside it than in the African jungle. I recall Brian Aldiss’ first novel, The Brightfount Diaries, was set here; he had worked in the shop during the 1950s.

The bookselling war horse that was Thornton’s was positioned like a trade gendarme in the centre of the Broad; for those in its orbit, it set high standards. By this time it was in its dotage, old man Thornton similarly (he it was dozing at its back desk, I was told), and was recklessly tumbledown. Various tributaries flowed from its cashpoint delta, arranged as defiantly as a musical coda with no resolution as its cash desk notched up sales after sale. A rostrum of rooms, big or small, that had as many books laid on the floor in front of the book shelves as upon them, were connected by staircases, resting spaces to recover your breath, and each similarly littered with nooks and crannies, some so tight that you could barely breathe when inside them. It was a many tiered, multi-volume scrum that defied health and safety yet always made perfect sense to the true bibliophile. He or she needed no compass to steer a course from reportage to belles lettres, through the literary criticism, stopping off at French modernist poetry, though never finding a fire exit along the way – the shop’s undoing in the end for it was closed. The shop may have been less exciting than I describe, but I fancy it may have taken Stanley longer to find Livingstone inside it than in the African jungle. I recall Brian Aldiss’ first novel, The Brightfount Diaries, was set here; he had worked in the shop during the 1950s.

The more functional and economical Robin Waterfield’s was toward the railway station and escape to the outside world. It had a broom cupboard first floor entrance which was in denial of its vast stretch above and beyond. It paraded itself as the antidote to pretension by mixing the commonplace with the august, confusing the cheap and tatty with the collectible and prized, but this supposed regard for book governance, its love of democracy and the common man, was a cynical strategy, all too commercial and much too careless: I didn’t think that much of the shop and am not sure why that was so, but I assumed that they paid for their stock by the weight rather than by content (and when I sold books to them later, I discovered that in fact they did – the weightier the collection, the less they paid, the perfect antidote to ordinance and good sense). I felt it improved greatly when the shop repositioned at the bottom of the High in a tight, confined space, and it took on more didactic ways; in fact its final owner closed the shop to become a teacher.

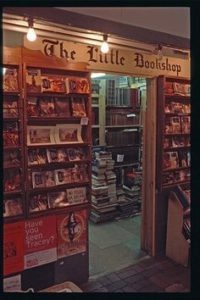

For the armchair revolutionary there was The Little Bookshop in the covered market off the High, an unwholesome, chaotic mash of used claptrap – Lenin, Trotsky, endless paperback sets of Braudel’s The Mediterranean World at bargain price, Mills and Boon, all sorts – but in retrospect remembered anecdotally and affectionately so often for startling finds (and for the wonderful Garon Records next door). Further away up the Cowley Road were occasional smatterings of real radicalism, feminism and the arcane. The Inner Bookshop on the Magdalen Road was a lone survivor, now gone.

For the armchair revolutionary there was The Little Bookshop in the covered market off the High, an unwholesome, chaotic mash of used claptrap – Lenin, Trotsky, endless paperback sets of Braudel’s The Mediterranean World at bargain price, Mills and Boon, all sorts – but in retrospect remembered anecdotally and affectionately so often for startling finds (and for the wonderful Garon Records next door). Further away up the Cowley Road were occasional smatterings of real radicalism, feminism and the arcane. The Inner Bookshop on the Magdalen Road was a lone survivor, now gone.

I recall also Robert Maxwell’s innovatory shop on the Plain that sold new books only (and typewriters). It had sofas and other obstacles positioned around its looped staircase, and here coffee was served. I went there several times and remember it as homely but smart. I was surprised to read that it had closed as early as 1972, though not surprised that it had traded at a severe loss, just as had Maxwell’s innovatory book wholesale escapade in the 1950s. That man made a great living from loss.

There were two Catholic bookshops off the bottom of St Aldate’s which I loved; one proudly sold Graham Greene novels, the other obviously had excommunicated him. Both of them were staffed by Evelyn Waugh lookalikes with horn-rimmed glasses. They dispensed their wares as though Communion bread; as a rule, only serious-minded books were sold, so literary transubstantiation involved no doctrinal dumbing down. The lesson I drew from these shops is that you can have too much of Chesterton’s humour, which drops to the floor like rosary beads, and the earnestness of these shops made me realise how much I loved Barbara Pym’s back pew giggling in the parish church. To cater for this Anglican taste, plenty of non-heretical bookshops could be found in Oxford as well. These accommodated high church sermons, the highbrow and high table manners, and were frequented by the many apologetic Anglican vicars who still today chase Oxford’s streets like packs of dogs; pince-nez are poised on their noses like parables, and ill-fitting dog collars keep them on the leash so they never stray past the beatitudes sold in Boswells, Oxford’s only department store.

Remainder bookshops sprung up slapdash like daffodils in spring only to wither as quickly. It seemed as though every book ever published was available somewhere in Oxford at that time.

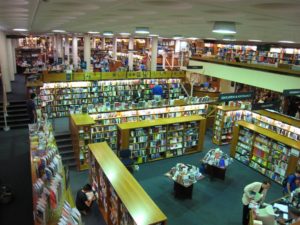

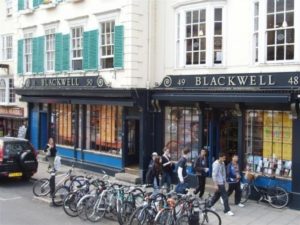

And, of course, the Mecca of the trade. Basil Blackwell’s, still owned until recently by the founder’s family, which at times in its history had threatened to ram the city with bookshops. It had a military bearing and waged a war on several fronts. Its gargantuan headquarters were at one end of Broad Street leaning against the Weston Library and dug in just as deep, prepared as though for battlefield skirmish. The  Norrington Room, the biggest commercial book bunker in the world, is a war room trench tunnelled deep under Trinity College; clearly its dimensions are based on the battlefield at Agincourt (and each St. Crispin’s Day the current Mr. Blackwell will charge the French by donating a hefty part of his dividend to UKIP). Sprawling the length of the Broad were Blackwell’s reconnaissance satellites and these sold new books only. Parker’s on the opposite side of the road to the main shop was select and precise, its shoes polished to cater for Blackwell’s library clientele. The paperback shop defied martial law and curfew, and opened dangerously late into the early evening. The children’s outpost further down, its recruiting office, was not as avuncular as it might be; it was designed, of course, for anyone but children. (Grandmother and great aunts buy most children’s books, only booksellers know that.) But the jewel of Blackwell’s military machine, for me at least, was the music shop in Holywell Street which whiled away many of my hours each week, a musical slot machine that I fed with much of my grant money. I would ricochet around its vinyl stash, and, three to the bar, sashay round its second-hand sheet music which curled its basement mezzanine like an interminable Chopin Waltz. The music department today is a melee of excellence, specialist knowledge and unbelievable service: it is hard to imagine that there is a better shop in the whole of Britain. Second-hand stock was housed in the main shop on the top floor. Its buying policy for used books was insane. You were made to queue and wait whilst their two buyers interrogated the books as though at court martial. They paid by the footnote. A fortune could be made with recently published heavyweight opus, and I had no idea how they got to make much money out of the transaction; its philosophy could be traced perhaps back to tenth century almshouses, its design to keep impoverished students fed. Blackwell’s had also an antiquarian bookshop housed out of Oxford. The manor house in Fyfield was heavy duty and not for the faint-hearted; it was where the nouveau aquatint aristocracy gambled its inheritance on copperplate and tooled leather binding.

Norrington Room, the biggest commercial book bunker in the world, is a war room trench tunnelled deep under Trinity College; clearly its dimensions are based on the battlefield at Agincourt (and each St. Crispin’s Day the current Mr. Blackwell will charge the French by donating a hefty part of his dividend to UKIP). Sprawling the length of the Broad were Blackwell’s reconnaissance satellites and these sold new books only. Parker’s on the opposite side of the road to the main shop was select and precise, its shoes polished to cater for Blackwell’s library clientele. The paperback shop defied martial law and curfew, and opened dangerously late into the early evening. The children’s outpost further down, its recruiting office, was not as avuncular as it might be; it was designed, of course, for anyone but children. (Grandmother and great aunts buy most children’s books, only booksellers know that.) But the jewel of Blackwell’s military machine, for me at least, was the music shop in Holywell Street which whiled away many of my hours each week, a musical slot machine that I fed with much of my grant money. I would ricochet around its vinyl stash, and, three to the bar, sashay round its second-hand sheet music which curled its basement mezzanine like an interminable Chopin Waltz. The music department today is a melee of excellence, specialist knowledge and unbelievable service: it is hard to imagine that there is a better shop in the whole of Britain. Second-hand stock was housed in the main shop on the top floor. Its buying policy for used books was insane. You were made to queue and wait whilst their two buyers interrogated the books as though at court martial. They paid by the footnote. A fortune could be made with recently published heavyweight opus, and I had no idea how they got to make much money out of the transaction; its philosophy could be traced perhaps back to tenth century almshouses, its design to keep impoverished students fed. Blackwell’s had also an antiquarian bookshop housed out of Oxford. The manor house in Fyfield was heavy duty and not for the faint-hearted; it was where the nouveau aquatint aristocracy gambled its inheritance on copperplate and tooled leather binding.

Blackwell’s all those years ago was at ease with its donnish fervour, speckled like dense dust on its shop fitting and stock. It is not quite so couth and shevelled today, for there is a sense of unease, a sense that its staid ownership, weighted with family resolve and the laziness of inherited wealth (and its building’s freehold), tussle with its enthusiastic and keen staff. I get the impression that each member of staff start their employment here with vaulting ambition, climb the junior ranks, earn enough above the minimum wage to survive modestly, then wilt as their ideas and gusto are met with the blank wall of tradition and rigidity. Retail rigor mortis had all but set in. Blackwell’s in its modern times could be likened to a dog straining to go fetch, but nobody has been throwing it a ball. Its library business must be more or less secure, at least while the excess of libraries in Oxford retain analogue breath; this part of their trade relies on the philosophy that made Coleman’s excessively wealthy – more mustard is left on the side of the plate than is ever tasted, and similarly most of the books in Oxford’s libraries are like skeletons in their graveyard vaults: their covers are rarely, if ever, prised apart.

Blackwell’s all those years ago was at ease with its donnish fervour, speckled like dense dust on its shop fitting and stock. It is not quite so couth and shevelled today, for there is a sense of unease, a sense that its staid ownership, weighted with family resolve and the laziness of inherited wealth (and its building’s freehold), tussle with its enthusiastic and keen staff. I get the impression that each member of staff start their employment here with vaulting ambition, climb the junior ranks, earn enough above the minimum wage to survive modestly, then wilt as their ideas and gusto are met with the blank wall of tradition and rigidity. Retail rigor mortis had all but set in. Blackwell’s in its modern times could be likened to a dog straining to go fetch, but nobody has been throwing it a ball. Its library business must be more or less secure, at least while the excess of libraries in Oxford retain analogue breath; this part of their trade relies on the philosophy that made Coleman’s excessively wealthy – more mustard is left on the side of the plate than is ever tasted, and similarly most of the books in Oxford’s libraries are like skeletons in their graveyard vaults: their covers are rarely, if ever, prised apart.

To such a lofty, clever and reverential hinterland, Blackwell’s will appeal still for it has the cache of tradition. And tradition is Oxford’s clarion call: each don spends dutifully their book allowance in this shop. It deserves this support, of course, for it stands firm in the face of modern-day assault and is loaded with intent. Its rooms, walls, shelves of books are lined with alphabetic purpose and sit upright as guardsmen on duty; to parade around its syllabary soup is a Grand Literary Tour, and it boasts the most impressive flock wallpaper in this country. If Blackwell’s no longer thrives as it did once (its accounts are unshook foil and tempered by lame excuse each annual general meeting; with their square footage, family patronage and loyal support it might do better), it can still almost hold its own. Like a punch drunk boxer it spars in the ring because it has never been trained to fall to the canvas. It is recently bought by Waterstones, that clueless empire.

To such a lofty, clever and reverential hinterland, Blackwell’s will appeal still for it has the cache of tradition. And tradition is Oxford’s clarion call: each don spends dutifully their book allowance in this shop. It deserves this support, of course, for it stands firm in the face of modern-day assault and is loaded with intent. Its rooms, walls, shelves of books are lined with alphabetic purpose and sit upright as guardsmen on duty; to parade around its syllabary soup is a Grand Literary Tour, and it boasts the most impressive flock wallpaper in this country. If Blackwell’s no longer thrives as it did once (its accounts are unshook foil and tempered by lame excuse each annual general meeting; with their square footage, family patronage and loyal support it might do better), it can still almost hold its own. Like a punch drunk boxer it spars in the ring because it has never been trained to fall to the canvas. It is recently bought by Waterstones, that clueless empire.

Today it is less sombre in aspect, though the finish of its décor is chosen still, I imagine, from an undertaker’s office. It is also less deferential and has no circular front desk with its team of respectful staff, as it did decades before, each staff mimicking the aspect of a porter or scout in one of the colleges. You can expect democratic service now, for the common folk are allowed to step forward as importantly as the professor standing impatiently behind me in the queue; this wasn’t always the case. And yes, it still has modest queues, perhaps because it has less staff!

In my youth its entrance was as a grand vestibule as auspicious as a railway station once was and as solemn as the bank manager’s waiting room; all was hushed reverence as a welter of staff pilfered the filing cabinets to locate details of your account. To open a Blackwell’s account was a rite of passage in your University life, second perhaps to acceptance as a member of the Bodleian Library. The only book I ever took on account was A J P Taylor’s wonderful book on the Hapsburg Empire, Bismarck and German unification, his clipped style and roving eye elevated otherwise dreary tales of diplomatic and military middle Europe to flights of imagination. I made such a hash of settling the account that I was too ashamed to use it again, proof that I was destined never to be a future Bismarck.

There are fewer foot soldiers today in Blackwell’s front trenches. Computers have replaced archaic filing systems, gigabytes have replaced stencilled pro forma and its day books. Even so, the modern retail experience involves waiting always. This experience was called cash and wrap when I was a youthful, budding retail entrepreneur; these days either almost doesn’t exist, for cash is all but moribund and the bag’s absence saves the planet apparently. The shop’s customer service desk is now on its top, second floor and at the furthest point from the stairs. An empty desk greets customer arrivals forlornly, a buzzer sits shyly upon it. All staff there are hidden, their tomed troglodyte world better than the real one, which is crazy with credit cards and ruined by complaint and illiteracy. On purpose Blackwell’s has made it an ordeal to complain; it anticipates the contemporary consumer’s right to bland service, nothing too bespoke, and these days complaint is indulged only by social justice warriors. Besides, a business cannot cost in customer service these days. The bricks and mortar experience today can be as anodyne and anonymous as its digital counterpart, and the homogeneous High Street can be supremely uninteresting. The civilized world plays hide and seek with this High Street sacrilege of care.

One other feature of this landscape was the book fair, which has all but disappeared. Routinely a motley troop of specialist dealers assembled in village halls dotted around Oxford or inside the city’s posh hotel foyers: the less cerebral Provincial Booksellers Fairs Association, the more venerable Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association which would meet at the Randolph Hotel. To join the ABA was as demanding as MENSA. Once accepted, a member was expected to dress like a quarter bound folio edition with bow tie and a shirt cut from marbled endpaper. The Association’s members had probably been school prefects and first team rugby players who, removed from their school greenhouse of promise and ill-prepared to be potted on into the world outside, had bolted like lettuce left in the ground until late September. To a man they all took to drink. They had immense corporations decorated with pocket watches and chains. They knew who Jorrocks and Samuel Richardson were, and were usually so dotty or half-cut that they assumed everybody else did too. The death of the Royal Mail and of its printed matter rate (the specialist book dealer sold often from mail order catalogue), as well as their bibulous aspect, killed off many of these booksellers. Nonetheless it is only antiquarian books that have held their value over the decades, unlike most other second-hand books whose financial worth nosedives by the hour.

Forty years later and Oxford is denuded of this myriad of bookshops. The second-hand book world now resembles hyper-inflationary Weimar Germany in reverse: a wheelbarrow of books cannot be traded even for a loaf of bread. Apart from a specialist shop in St Aldate’s, the charity shops which feast off donations and enjoy free labour and rate relief, and Blackwell’s, there is only one second-hand bookshop in Oxford left, 2018, and that sells all sorts else as well. Aptly called The Last Bookshop, its name is a self-conscious skit on the state of its commercial milieu.

The internet is probably the main cause for this decline, although I am not so sure we should credit it with every change in society. Sometimes a coiled string will unravel of its own accord. The book itself has come to represent something different to its previous life. Indeed the book is a parody of its former worth.