September 2019

September, 2019, Dolgellau

I HAVE LEFT MACHYNLLETH clock tower to head north. The bus bobs and bends, ricochets the Llefenni Valley and its ramshackle slate villages, settlements wedded intermittently by narrow railway and river. The fractal blur of tarmac that carves a way through to Dolgellau has waterfalls hanging either side that drop like pearl earrings. Vistas open and close as the bus wends its way in-between hills and peaks; these might stretch forever if it weren’t for the horizon. Stone walls course either side of the road topsy-turvy. I take in some detail along the way – trees that menace the side of the road like highwaymen, sheep meandering on the precarious slopes. Above is a trance-like beauty that fills a heart with joy whenever seen: a net of sky, a rich palette of periwinkle and powder blue tufted like soft parchment, splashes of tangerine and carrot, purple prose streaked with puffs of chiffon cloud. A beautiful, beatific tableau.

The bus has rattled to Dolgellau. Reflex takes me first to the main hotel where I drink coffee, and where I gaze upwards to Cader Idris. This mountain stands sentry-like over the town. It is said that anyone who sleeps alone on the slopes of this ancient stronghold, which is shaped like a chair and has a scree summit and surround of supposedly bottomless lakes, will wake as either madman or poet. I am not sure I could tell the difference, having spent the previous dozen years arranging poetry readings in Oxford: tongues of fire on Idris flaring.

The bus has rattled to Dolgellau. Reflex takes me first to the main hotel where I drink coffee, and where I gaze upwards to Cader Idris. This mountain stands sentry-like over the town. It is said that anyone who sleeps alone on the slopes of this ancient stronghold, which is shaped like a chair and has a scree summit and surround of supposedly bottomless lakes, will wake as either madman or poet. I am not sure I could tell the difference, having spent the previous dozen years arranging poetry readings in Oxford: tongues of fire on Idris flaring.

DOLGELLAU, ONCE SPELT DOLGELLEY, sits in the sparse yet verdant landscape of Snowdonia wrapped in a coat of many grassland colours. The geological mayhem of sedimentary rock, volcanic ash and igneous intrusion that comprise Snowdon itself is more than impressive. The tender landscape in these southerly parts may be interpreted to be more the hair of the dog that bit, not the dog itself, but it will bark politely if you tell it that, for in modesty beauty is found best. There is a sprinkle of the divine when you walk from the outskirts of the town in any direction. For sure, God smiled on this jigsaw of farming land.

Modesty can be found, too, in Dolgellau’s slapdash sprawl of suburban design. It contains over 200 listed buildings, the densest collection in the whole of the United Kingdom. In 1798, Rev J Evans wrote that the town’s “streets were irregular and very narrow, and the houses small and ill lit.” Thirty years after this mean observation, an urban focus had formed to foster a less haphazard shape of settlement. This kicked off after the first bank was established in 1803, and Eldon Square became the town’s overhauled nexus. Its concentric orbit battled to make sense of a cross-hatched labyrinth of cut throughs and up-ways strung like a lasso. These thoroughfares are threaded with chimney stacks and slate roofs slung low like cloth caps that tumble, often askew, above severe dolerite brickwork – “a tight tumble of grey stones that might almost have fallen there in an avalanche,” wrote Jan Morris. These patched hopscotch patterns of stone can be claustrophobic, but flowers in pots, bunches of curated wild flower, colourful doorways and lattice-worked porches offer relief.

The town developed, I think, more by individual munificence than by communal resolve. At some point in the nineteenth century, Dolgellau’s aspect of civic compliance and neighbourly agreement took shape. The penal reformer John Howard visited the town in 1773 and was concerned by the state of the gaol. Prisoners not long after petitioned about maggots and other “nasty filth in the water,” drawn from the River Arron which was used to wash sheep skin. But less than a hundred years later, the gaol was closed because of a dearth of occupants. Sin is a different thing but crime was seemingly done away with here.

The economic well-being of Dolgellau has rested historically on wool and tanning. Many of today’s larger houses are converted mills. Tanning was messy business and the stench once travelled via the drains all over town; Dolgellau earnt its nickname – the ‘stinky town.’ Other scratch attempts to employ a workforce were fitful, then the gold rush. The lode was discovered in 1860, mined rigorously from 1884 and closed in 1998 when pollution and health and safety made it too costly. Royal wedding rings from 1934 have been made from this gold, and the Windsors own a nugget of the mine’s prized bounty still. A new lode was discovered recently and the lengthy task of obtaining permissions to open the mine has started. The latter-day prospectors are housed in the building next to my shop. I have determined to dig a tunnel into its vault (and if I surface in its toilet rather than its vault, I shall be crestfallen).

By 1900 the gold and also copper mines gave 500 miners employment. The town’s most successful retailer, the ironmonger T H Roberts, made a fortune from selling panning utensils. This shop, with its four enormous first floor windows that gape like a quadraphonic Cyclops, has its original counter and accounting room still, and the original floor to ceiling stained pine shelves. These are no longer littered with shovels and pickaxe but jam and coffee: today it is a splendid café that serves a breakfast to die for. The ceilings are high so the building is always cold, and a winding staircase leads to a first floor overspill. Above that is storage leading up to an artist’s studio nestled in the roof space, long deserted yet brushes and easel are still in place. Eye-catching buildings often disappoint (though not this one), and many of the piles in Dolgellau will be ridden with damp or in need of propping up.

Adjacent to Roberts is Siop Hughes, an outfitter and fashion emporium. It buys its cloth today from Manchester as it always did; opposite stands London House, so-called because it would source its goods from London. Siop Hughes opened in 1854. The sixth generation runs the business now and the grandfather worked there until recently, back seat but modestly proprietorial and expansive. He reminisces of childhood fears, of how the ironmonger next door kept dynamite in his cellar. Perhaps this nightmare of exploding sulphur encourages Siop Hughes to scatter Biblical tracts amongst the underwear stand and umbrellas at the shop entrance; there is also a forbidding sense of the eternal amongst its nylons. Twice every Sunday, poorly attended, the shop resurrects itself as a makeshift Baptist Church, no hymns and a humdrum sermon of repentance.

Standing on a paved eyrie above the town’s concourse and looking down on the sunken vale in which Dolgellau rests, one can glimpse its holy spaces of devotion and its hushed graveyards with no dominion but many denomination: the parish church with its lazy vicar, a Catholic enclave and a plethora of Nonconformist, Methodist and Baptist chapels, one built every step of the Welsh revival that set to in 1859 and came to rest in 1905. A concertina of birth, baptism, wedding and death. I count eleven holy spaces, most closed, many others, I am told, have long gone.

Dolgellau is a small community yet it contains a kaleidoscope of offer. Linoleum sold by the roll, a microwave or even a brand new Ford motorcar, guitars, pots of lovage, chocolate cracknel made locally, drills and hammers, wall tiles, jewellery and homemade pies, not forgetting, of course, the sheep and rusty tractors at the weekly farm auction. There is an excellent wool shop, a residue of the town’s past, and an outstanding wine bar, five full pubs, and cafes galore. A self-sufficiency of sorts. This small-town tented village is, I imagine, a summary of what I ignorantly construe to be a Welsh ethos of self-containment. It has shovelled out coal and its stash of minerals, sold its sheep and cattle, but there appears to be little need to broadcast its true cultural self. Dolgellau has a circular contentment and is satisfied to exist within its own footprint. That’s a confidence not found readily elsewhere.

Today it is possible that only shepherds and milkmaids have all-year employment. Many run a B&B or are occupied with seasonal tourism. There are few shops empty at present, but over the years its retail square footage must have been pulled on and off like long johns as the town struggled to balance the needs of a summer tidal wave – day trippers, cyclists, backpackers, mock mountaineers – and its meagre population. The 2011 census listed 2,688 residents, and this figure hadn’t changed much for decades.

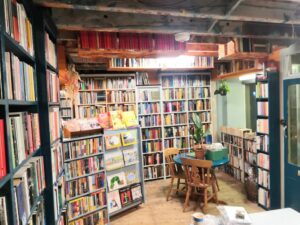

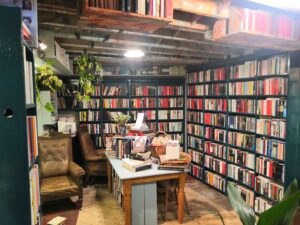

The shop I have taken on has been empty, off and on, for some years. Its front door is older than me: six different layers of contrasting paint were revealed while sanding it down. The shop fascia boards were stacked like playing cards with trading names placed on top of each other, a palimpsest of trade. Early last century, bootmakers took residence. I don’t think it was a shop then, but passersby call in to recite subsequent memory of buying antiques, haberdashery, a haircut, and most suggest that nothing had worked convincingly since the sweet shop of yesteryear, its longest use. This building housed a slalom ride of business that, after recent use as charity shop, has crashed to bookshop.

Alas, books cannot compete with sherbet, not even with liquorice. How this bookshop fares will be interesting.