Books To Take To A Desert Island

The Holy Bible, King James Version

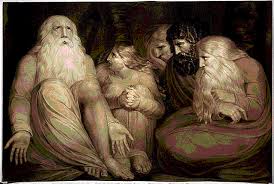

God, the Maker of my Despair

The Bible’s glow is immense. It lives on in Milton, it is the key player in Shakespeare, it breathes fantastically through Blake, its sophistry informs the world of Middlemarch, its disappointment ebbs and flow in Eleanor Rigby. At any time in our Albion timeline, stop the watch and you will see how the Bible underpins our world view. Yet today we tend to express chagrin at the remnants of Christian thought, Peter Hitchens and Songs of Praise its last resting points perhaps. In a psychedelic haze of marijuana, the Maharishi and their wealth of millions, The Beatles trudged eastward, and since then we pay Christian ideal lip service only. Shame, say I.

The Bible’s glow is immense. It lives on in Milton, it is the key player in Shakespeare, it breathes fantastically through Blake, its sophistry informs the world of Middlemarch, its disappointment ebbs and flow in Eleanor Rigby. At any time in our Albion timeline, stop the watch and you will see how the Bible underpins our world view. Yet today we tend to express chagrin at the remnants of Christian thought, Peter Hitchens and Songs of Praise its last resting points perhaps. In a psychedelic haze of marijuana, the Maharishi and their wealth of millions, The Beatles trudged eastward, and since then we pay Christian ideal lip service only. Shame, say I.

That the Bible is still a holistic source of nourishment is obvious for all to see and, our multicultural vistas notwithstanding, it remains the focal point of our civilization. The Bible should be compulsory reading. The storytelling, especially in the bold and unforgiving Pentateuch, is astonishing; the astonishing reverie in The Apocalypse of John so absurdly eschatological as to be surrealist and poetic; the poetry in The Psalms so full of bright warmth as to shine as a star bright enough to steer any ship through the darkest night: shine on. Amen, say I.

The Complete Works

William Shakespeare

Shakespeare dedicated The Sonnets to “Mr W.H,” and some say that he was the Earl of Pembroke, colourful and portly, the sculptured chap who holds court in the Bodleian Library Old Schools Quad, an expensive bit of kit by Rubens. The First Folio of Shakespeare is dedicated to him and his brother – and Pembroke was stark contrast to Sir Thomas Bodley, the earlier éminence grise of the Bodleian, a drab and holy man who forbad Shakespeare’s manuscripts entering the Library, because theatrical meant ungodly, but also because for all his intention and enterprise Bodley was a dull man, a man you would not wish to sit next to at a garden fete. But not until Bob Geldof (the only man ever to have gotten both Pepsi Cola and Coca-Cola to sponsor the same event) was there such a deal broker: Bodley it was who got the Stationers’ Company in London, the King’s ersatz censorship unit, to send a free copy of every manuscript submitted for publication to the Library. (It hasn’t paid a penny for its books since then.)

Shakespeare dedicated The Sonnets to “Mr W.H,” and some say that he was the Earl of Pembroke, colourful and portly, the sculptured chap who holds court in the Bodleian Library Old Schools Quad, an expensive bit of kit by Rubens. The First Folio of Shakespeare is dedicated to him and his brother – and Pembroke was stark contrast to Sir Thomas Bodley, the earlier éminence grise of the Bodleian, a drab and holy man who forbad Shakespeare’s manuscripts entering the Library, because theatrical meant ungodly, but also because for all his intention and enterprise Bodley was a dull man, a man you would not wish to sit next to at a garden fete. But not until Bob Geldof (the only man ever to have gotten both Pepsi Cola and Coca-Cola to sponsor the same event) was there such a deal broker: Bodley it was who got the Stationers’ Company in London, the King’s ersatz censorship unit, to send a free copy of every manuscript submitted for publication to the Library. (It hasn’t paid a penny for its books since then.)

So should we wish to be Pembroke or Bodley? The first was a bit of a brag and a lot of a rake, but also open and warm – for he had the Bard in his life. Bodley is a man who married for wealth ahead of beauty; to wake up each morning next to a trunk of bank notes is probably not so much fun in the end.

Shakespeare is writ large in our every day, in every common or uncouth sentence, and every wise saying. He is the fountainhead of our language, the geezer who made it rich and varied, colloquial yet highfalutin, exact yet vague when we need it to be.