Books To Sing & Dance To

Prufrock & Other Observations

T. S. Eliot

A copy of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock once hung on the inside of the Albion Beatnik Bookstore toilet door. It is a poem that should be included in any anthology of poetry read best in the loo and, as everyone knows, T.S. Eliot is an anagram of toilets, and that the poem’s hero should be called J. Alfred Pisspot. The poem is a delight, the words skip off the page. The pages are blotting paper to the projected thought of their reader (is like the patchwork ambiguity of Lennon and McCartney), is about everything and nothing – although it pertains specifically to Prufrock’s response to his frustrations, lost opportunities, thwarted desires, regret, weariness, sexual lassitude, in fact the angst-ridden inertia of a failed life, Lennon and McCartney’s A Day in the Life of the universal man and woman. A specific failing in unrequited love, or a meaningless existence in a modern world that makes no sense, or anything in between. The poem’s wonder is that it sparkles on the page, and this comes to the fore when it is recited out loud. The clash of vocabulary and the meld of beauty and formality, the ethereal and the mundane, makes it awesome.

A copy of The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock once hung on the inside of the Albion Beatnik Bookstore toilet door. It is a poem that should be included in any anthology of poetry read best in the loo and, as everyone knows, T.S. Eliot is an anagram of toilets, and that the poem’s hero should be called J. Alfred Pisspot. The poem is a delight, the words skip off the page. The pages are blotting paper to the projected thought of their reader (is like the patchwork ambiguity of Lennon and McCartney), is about everything and nothing – although it pertains specifically to Prufrock’s response to his frustrations, lost opportunities, thwarted desires, regret, weariness, sexual lassitude, in fact the angst-ridden inertia of a failed life, Lennon and McCartney’s A Day in the Life of the universal man and woman. A specific failing in unrequited love, or a meaningless existence in a modern world that makes no sense, or anything in between. The poem’s wonder is that it sparkles on the page, and this comes to the fore when it is recited out loud. The clash of vocabulary and the meld of beauty and formality, the ethereal and the mundane, makes it awesome.

Eliot began to write The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock in 1910, although it was published in the June 1915 issue of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, later published in a twelve-poem chapbook, Prufrock and Other Observations. This is the coming of age of Eliot, the point of his arrival as one of the major poets of the twentieth century, steering poetry away from late nineteenth century romantic verse and Georgian lyrics to Modernism.

The Horse’s Mouth

Joyce Cary

Cary was a fabulous writer, fuelled by stark originality and a dedication to his craft. His books fizz and throb with energy, always on the cusp of brilliance even if never quite there. The Horse’s Mouth is his most enduring book (it became a great film with Alec Guinness), and is the third part of a trilogy. The series is not sequential, rather each book concentrates on one character whose life intertwines with the other two, and each character makes ‘guest’ appearances in the other books (Herself Surprised and To Be A Pilgrim).

Cary was a fabulous writer, fuelled by stark originality and a dedication to his craft. His books fizz and throb with energy, always on the cusp of brilliance even if never quite there. The Horse’s Mouth is his most enduring book (it became a great film with Alec Guinness), and is the third part of a trilogy. The series is not sequential, rather each book concentrates on one character whose life intertwines with the other two, and each character makes ‘guest’ appearances in the other books (Herself Surprised and To Be A Pilgrim).

He wrote often in the present tense and, not always well edited, mistakes in use of tense can sometimes be found. His style of writing consisted of gobbets of writing, snatches of text that were then bolted together, a cut and paste method that predates word processing by many decades. But it afforded also opportunity for technical glitches. He would overwrite for each book, and gradually would assemble the novel by culling his screed.

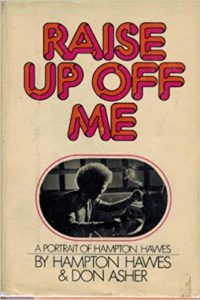

Raise Up Off Me

Hampton Hawes

Hampton Hawes, who died aged 49 in 1977, was one of the greatest jazz bebop pianists. But at the summit of his career, celebrated as New Star of the Year by Down Beat magazine in 1956, he had already a drug addiction that would lead to arrest and imprisonment. A career that had blossomed early with the greatest players of his day was knocked off its rails and, even though President Kennedy was to grant an executive pardon in 1963, was never to recover. In eloquent and humourous tone, Hawes tells of a life of suffering and redemption that reads like an improbably fast-paced and demotic novel. Raise Up Off Me, published in 1974, remains one of the most enduring, most embroidered (!) and best first-hand accounts of the jazz life ever written.

Hampton Hawes, who died aged 49 in 1977, was one of the greatest jazz bebop pianists. But at the summit of his career, celebrated as New Star of the Year by Down Beat magazine in 1956, he had already a drug addiction that would lead to arrest and imprisonment. A career that had blossomed early with the greatest players of his day was knocked off its rails and, even though President Kennedy was to grant an executive pardon in 1963, was never to recover. In eloquent and humourous tone, Hawes tells of a life of suffering and redemption that reads like an improbably fast-paced and demotic novel. Raise Up Off Me, published in 1974, remains one of the most enduring, most embroidered (!) and best first-hand accounts of the jazz life ever written.

Jazz saxophonist Art Pepper’s autobiography, Straight Life, is similarly chilling, his account of a now classic recording date immediately after release from prison, unforgettable. Julian Cope’s Head-on is a retelling of his years with Teardrop Explodes, but also a personal odyssey of a wannabe cult figure.

The Enchanted April

Elizabeth von Arnim

Four dissimilar women in 1920s England share a month stay in Italy, and rediscover hope and love in the beauty and calm of their environment. The end of the novel is beautiful and uplifting; more than that, it is magical.

Four dissimilar women in 1920s England share a month stay in Italy, and rediscover hope and love in the beauty and calm of their environment. The end of the novel is beautiful and uplifting; more than that, it is magical.

Similarly, and even with their false starts, mishaps along the way, or final tragedies, novels like L.P. Hartley’s The Go-Between or Carson McCullers’ The Heart is A Lonely Hunter can only be described as fulfilling and life affirming (a suicide is the conclusion to both!). It seems as though fiction can work on several levels of emotional entanglement at once, and can hold our better and aspirational thoughts to ransom. Take care however. Don Quixote died of an overdose of chivalry (he’d learnt that from books); Dorian Gray models himself on a character in a book (it “poisons” him); poor Leonard Bast, the aspiring littérateur in Howard’s End, struck by a sword it is true, dies under an avalanche of books (as he falls against a bookcase).