Books To Fly You To The Moon

Moby-Dick

Herman Melville

”Nobody had more class than Melville. To do what he did in Moby-Dick, to tell a story and to risk putting so much material into it. If you could weigh a book, I don’t know any book that would be more full. It’s more full than War and Peace or The Brothers Karamazov. It has Saint Elmo’s fire, and great whales, and grand arguments between heroes, and secret passions. It risks wandering far, far out into the globe. Melville took on the whole world, saw it all in a vision, and risked everything in prose that sings. You have a sense from the very beginning that Melville had a vision in his mind of what this book was going to look like, and he trusted himself to follow it through all the way.“ – Ken Kesey interviewed by The Paris Review in 1994

”Nobody had more class than Melville. To do what he did in Moby-Dick, to tell a story and to risk putting so much material into it. If you could weigh a book, I don’t know any book that would be more full. It’s more full than War and Peace or The Brothers Karamazov. It has Saint Elmo’s fire, and great whales, and grand arguments between heroes, and secret passions. It risks wandering far, far out into the globe. Melville took on the whole world, saw it all in a vision, and risked everything in prose that sings. You have a sense from the very beginning that Melville had a vision in his mind of what this book was going to look like, and he trusted himself to follow it through all the way.“ – Ken Kesey interviewed by The Paris Review in 1994

Melville’s career is a study in decline. After early success in the 1840s followed a precipitous career drop, and he was all but forgotten when he died in 1891. After the First World War the avalanche of Modernist hybrid aesthetic ensured that Melville’s kaleidoscopic vision was recognized for what it was: sharp shards of genius. Moby-Dick wrestles from the English lan-guage every nuance and meaning, with such a rich repertoire of technique, and to an effect so grand and all embracing that it makes its reader cry with overwhelming shouts of both joy and despair. It is the finest book written in the English language.

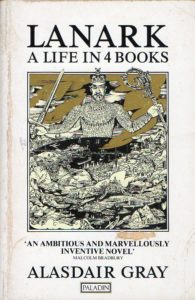

Lanark

Alasdair Gray

Gray began the writing of this monumental book in 1954 while a student; Book One was finished in 1963 but failed to find a publisher and the book was finished in 1976; it was published in 1981 and received praise immediately. It is a portrait of his home town of Glasgow, dystopian and surrealist.

Gray began the writing of this monumental book in 1954 while a student; Book One was finished in 1963 but failed to find a publisher and the book was finished in 1976; it was published in 1981 and received praise immediately. It is a portrait of his home town of Glasgow, dystopian and surrealist.

Gray is a fascinating writer. Only Anthony Burgess or John Fowles can be said to rival him for scope, and certainly not for originality. He draws on a rich tradition in British literature – Mervyn Peake, Wyndham Lewis, David Jones, Denton Welch, Joyce Cary – of using art as inspiration or even including it in the creation of the novel: Gray uses his own drawings and skillful use of typography as features of his books, and he started life as a scene and portrait painter. Will Self has referred to him as a “creative polymath with an integrated politico-philosophical vision;” Gray described himself as a “fat, balding, increasingly old Glasgow pedestrian.”

Ulysses

James Joyce

Ulysses (the Latinate name for Odysseus) was pub-lished in serial form from 1918, and by Sylvia Beach in Paris in 1922. It is the vade mecum of the Modernist school of writing (stream-of-consciousness flow, experimental prose full of riddle and pun), and it was a precursor of Fox Network’s 24, though I doubt agent Jack Bauer was modelled on Leopold Bloom (I don’t remember that Bauer spent so long on the bog). 16th June 1904 is Bloomsday.

Ulysses (the Latinate name for Odysseus) was pub-lished in serial form from 1918, and by Sylvia Beach in Paris in 1922. It is the vade mecum of the Modernist school of writing (stream-of-consciousness flow, experimental prose full of riddle and pun), and it was a precursor of Fox Network’s 24, though I doubt agent Jack Bauer was modelled on Leopold Bloom (I don’t remember that Bauer spent so long on the bog). 16th June 1904 is Bloomsday.

265,000 words is the book’s length, 30,030 is its rich lexicon, so a new word is introduced one in under every nine. It has been estimated that the first edition contained 2,000 errors, and it has been observed that this number has been added to with each subsequent edition. There have been eighteen editions for sure, often offering variation every time a new impression was printed. A New York pirated edition was published in 1929, the Odyssey Press edition in 1932 (held by some to be the least contentious); because of censorship battles it was published in England first in 1936 by the Bodley Head, later revised in 1960. The Joyce Estate has been somewhat baffled and become protective, commercially dumbing down and approving a Wordsworth edition for £1.99 ahead of copyright D-Day in the United Kingdom. To help excite scholarly interest Joyce had laid his own booby traps, incorporating error by design, and any edition of Ulysses therefore resembles the human condition, that is a rich and layered corpus of mistake, a state of original sin; even Gabler’s ‘corrected edition’ of 1984 turned out to be a literary Tiger Woods, a saintly winner exposed with pants down, and, like Woods, it was roasted for its faulty fundamentals as well as its faulty footnotes (though to be fair Joyce’s own iron play from the rough wasn’t that good), and most publishers have reverted to its 1960 (or 1922) text. John Kidd’s scholarly revision is yet to charge in as a knight in shining armour; it has been stalled by the Joyce Estate’s current lack of interest in further foraging with the text.

Originally Ulysses (the Latinate name for Odysseus) was published in serial form by the American journal The Little Review from 1918, and by Sylvia Beach in Paris in 1922. After a year’s break, Joyce set to on Finnegans Wake (no rest for the wicked), a book that in many ways is an even tougher nut to crack, an interpretation of dream landscape to be read by diehards only.

Originally Ulysses (the Latinate name for Odysseus) was published in serial form by the American journal The Little Review from 1918, and by Sylvia Beach in Paris in 1922. After a year’s break, Joyce set to on Finnegans Wake (no rest for the wicked), a book that in many ways is an even tougher nut to crack, an interpretation of dream landscape to be read by diehards only.

Nineteen Eighty-four

George Orwell

Orwell is the twentieth century version of Shakespeare: so much of his writing has strayed into common parlance. The adjective Orwellian is a policy of control by propaganda, surveillance and misinformation. In Nineteen Eighty-four Orwell described a totalitarian government that controlled thought by controlling language. Newspeak is an obfuscatory language designed to make independent thought impossible; doublethink means holding two contradictory beliefs simultaneously; the thought police are those who suppress all dissenting opinion; prolefeed is homogenized and manufactured media used to control; Big Brother is a supreme dictator who watches everyone.

Orwell is the twentieth century version of Shakespeare: so much of his writing has strayed into common parlance. The adjective Orwellian is a policy of control by propaganda, surveillance and misinformation. In Nineteen Eighty-four Orwell described a totalitarian government that controlled thought by controlling language. Newspeak is an obfuscatory language designed to make independent thought impossible; doublethink means holding two contradictory beliefs simultaneously; the thought police are those who suppress all dissenting opinion; prolefeed is homogenized and manufactured media used to control; Big Brother is a supreme dictator who watches everyone.

Orwell argued for clear speech and thought, a John the Baptist figure who forewarned of the terrible plagues of political correctness and identity politics that infects modern day life; he would no doubt have found it difficult to tolerate much errant thought of today, an era where power is pursued for its own sake, where political leaders have no rationale. Moreover we have no idea who Big Bruv is, but we know he exists.