Books To Come Of Age To

The Member of the Wedding

Carson McCullers

McCullers explained in a letter that this novel was “one of those works that the least slip can ruin. It must be beautifully done. For like a poem there is not much excuse for it otherwise.” Its streamline beauty, however, might mask the fact that this is a full-on existential novel, flooded with darkness, and written in 1946 at the same time as the wave of French and German writers were coming out of their starting blocks. The book is about far more than the coming of age of a young and troubled girl, Frankie, but very much about the tragic tristesse of post-adolescence. Sylvia Plath admired this book, and the phrase “silver and exact,” which describes train tracks in the novel, is the first line of Plath’s poem Mirror.

McCullers explained in a letter that this novel was “one of those works that the least slip can ruin. It must be beautifully done. For like a poem there is not much excuse for it otherwise.” Its streamline beauty, however, might mask the fact that this is a full-on existential novel, flooded with darkness, and written in 1946 at the same time as the wave of French and German writers were coming out of their starting blocks. The book is about far more than the coming of age of a young and troubled girl, Frankie, but very much about the tragic tristesse of post-adolescence. Sylvia Plath admired this book, and the phrase “silver and exact,” which describes train tracks in the novel, is the first line of Plath’s poem Mirror.

There is a whole European movement of existential writing that barely touched the English temperament of the time. Jean Paul Sartre’s Nausea and Albert Camus’ The Outsider are read now by many angst and acne ridden tender teenagers, but Celine’s Journey to the End of Night is the most arresting.

Lolita

Vladimir Nabokov

Nabokov was a one-off. He wrote first in Russian (he was born in St Petersburg), but his later and most famous writings were in English. He was a celebrated synesthete, a lepidopterist of renown, and a celebrated composer of chess problems. Lolita is riddled with wordplay and double entendres.

Nabokov was a one-off. He wrote first in Russian (he was born in St Petersburg), but his later and most famous writings were in English. He was a celebrated synesthete, a lepidopterist of renown, and a celebrated composer of chess problems. Lolita is riddled with wordplay and double entendres.

Described often as an erotic novel, its hero, Humbert, diffuses its tragic plot with humour. Essentially it is a study of lust, seemingly of an older man for a girl. In 1955, the year of its publication in France, Graham Greene singled it out as noteworthy and literary, whilst the Sunday Express editor called it the “filthiest book I have ever read,” and the Home Office seized all extant copies because of its pornographic content. Opinion is less divided now, content that it is both mucky and literary.

Other books that in their time caused furore, the lighter fuel of the teenage experience, include Anthony Burgess’ violent A Clockwork Orange, Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, and American Psycho by Brett Easton Ellis (these days the Billy Bunter stories also).

Gone to Earth

Mary Webb

Mary Webb’s novels are set in her familiar Shropshire landscape. Her family descended from Walter Scott (though we shouldn’t hold that against her) and she had ambitions for her writing that were sadly never met in her lifetime, though after her death Stanley Baldwin, when Prime Minister, referred to her as a “neglected genius,” and a handsome Collected Edition and popularity ensued.

Mary Webb’s novels are set in her familiar Shropshire landscape. Her family descended from Walter Scott (though we shouldn’t hold that against her) and she had ambitions for her writing that were sadly never met in her lifetime, though after her death Stanley Baldwin, when Prime Minister, referred to her as a “neglected genius,” and a handsome Collected Edition and popularity ensued.

Gone to Earth is the story of Hazel Woodus, a child of nature who loves wild animals and the weather and seasons of the countryside and wants simply to be herself. She is drawn reluctantly into the world of romantic human relationships through her great beauty, marrying a local church minister; she also becomes the object of the local fox hunting squire’s obsessive love. Hazel casts herself down a mineshaft to escape, clutching her beloved pet fox. Stella Gibbons’ fabulous Cold Comfort Farm was a parody of Mary Webb’s writings, and of other “loam and lovechild” writers like Sheila Kaye Smith (whose novels were set in Sussex), Mary E. Mann (Norfolk) and, much earlier, Thomas Hardy. “The large agonised faces in Mary Webb’s book annoyed me…,” wrote Gibbons. “I did not believe people were any more despairing in Herefordshire than in Camden Town.”

Evie And Guy

Dan Holloway

A highly original piece of writing, now in its second edition – if writing it is, for it is presented only in numbers and as far as is known is the first novel written in number form only (and as such it made Pseuds Corner in Private Eye). Guy and Evie’s biographies are presented consecutively, but only through their incidence of masturbation: each masturbatory act is dated, timed, even marked if not orgasmic, the two characters’ timelines can be compared. It is a remarkable feat of imagination not only to have written this book but also to read it: the novel is presented in skeletal form and no steer is given the reader, rather it is the reader who imposes reason and narrative to flesh out the story, his or her imagination (or ulterior knowledge, the weather for instance) brings light to the characters and their lives.

A highly original piece of writing, now in its second edition – if writing it is, for it is presented only in numbers and as far as is known is the first novel written in number form only (and as such it made Pseuds Corner in Private Eye). Guy and Evie’s biographies are presented consecutively, but only through their incidence of masturbation: each masturbatory act is dated, timed, even marked if not orgasmic, the two characters’ timelines can be compared. It is a remarkable feat of imagination not only to have written this book but also to read it: the novel is presented in skeletal form and no steer is given the reader, rather it is the reader who imposes reason and narrative to flesh out the story, his or her imagination (or ulterior knowledge, the weather for instance) brings light to the characters and their lives.

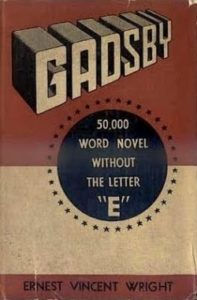

Evie and Guy is available now in its second edition. I’m reminded of Ernest Vincent Wright’s novel Gadsby (also peculiarly interesting for it contained no letter e – its inspiration was that he had wrenched this letter from his typewriter keyboard), published in 1939: it sold fewer that 50 copies but is now highly sought after and extremely valuable. Dan’s first edition is similarly an investment.

Evie and Guy is available now in its second edition. I’m reminded of Ernest Vincent Wright’s novel Gadsby (also peculiarly interesting for it contained no letter e – its inspiration was that he had wrenched this letter from his typewriter keyboard), published in 1939: it sold fewer that 50 copies but is now highly sought after and extremely valuable. Dan’s first edition is similarly an investment.